At the corner of 229th and Laconia Streets in the Bronx, the police precinct office faces a cluster of buildings mostly three-stories tall known as the Edenwald Houses. The Edenwald Houses, along with the nearby Eastchester Gardens, were the target this past April of what the U.S. Attorney trumpeted as the “largest gang takedown in New York City history.” One hundred and thirteen people were indicted, mostly young men in their twenties.

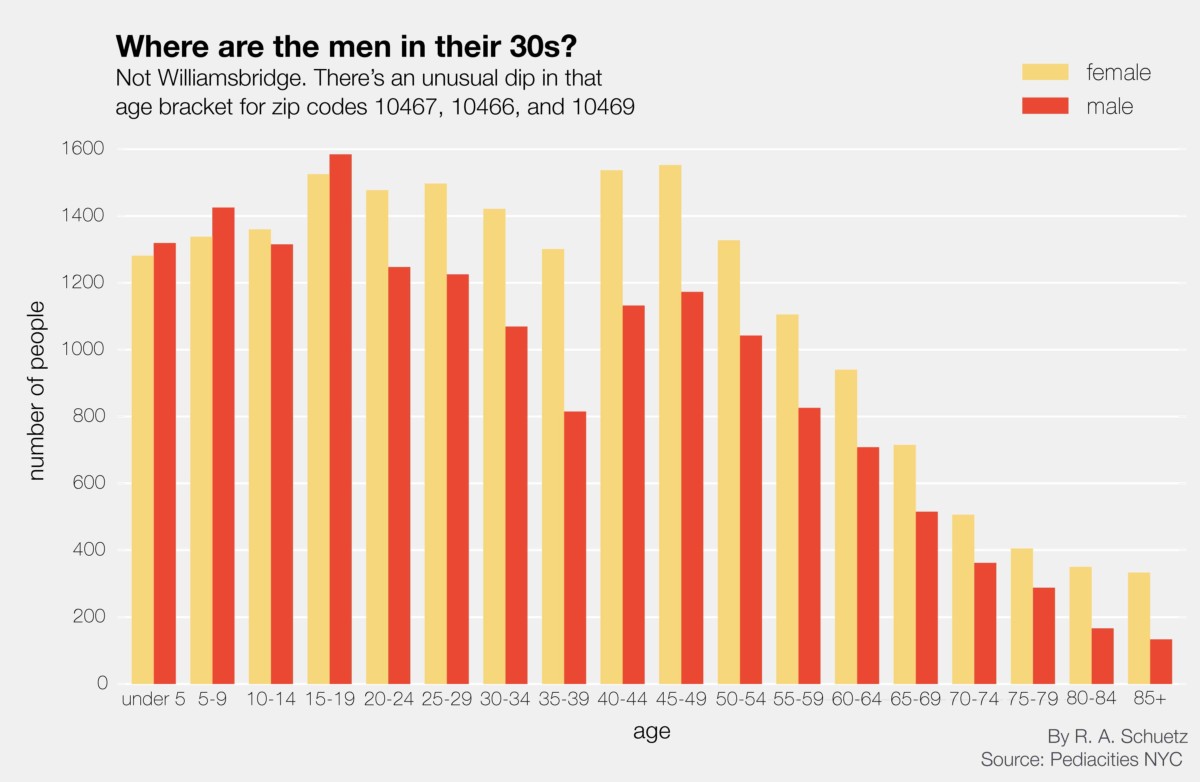

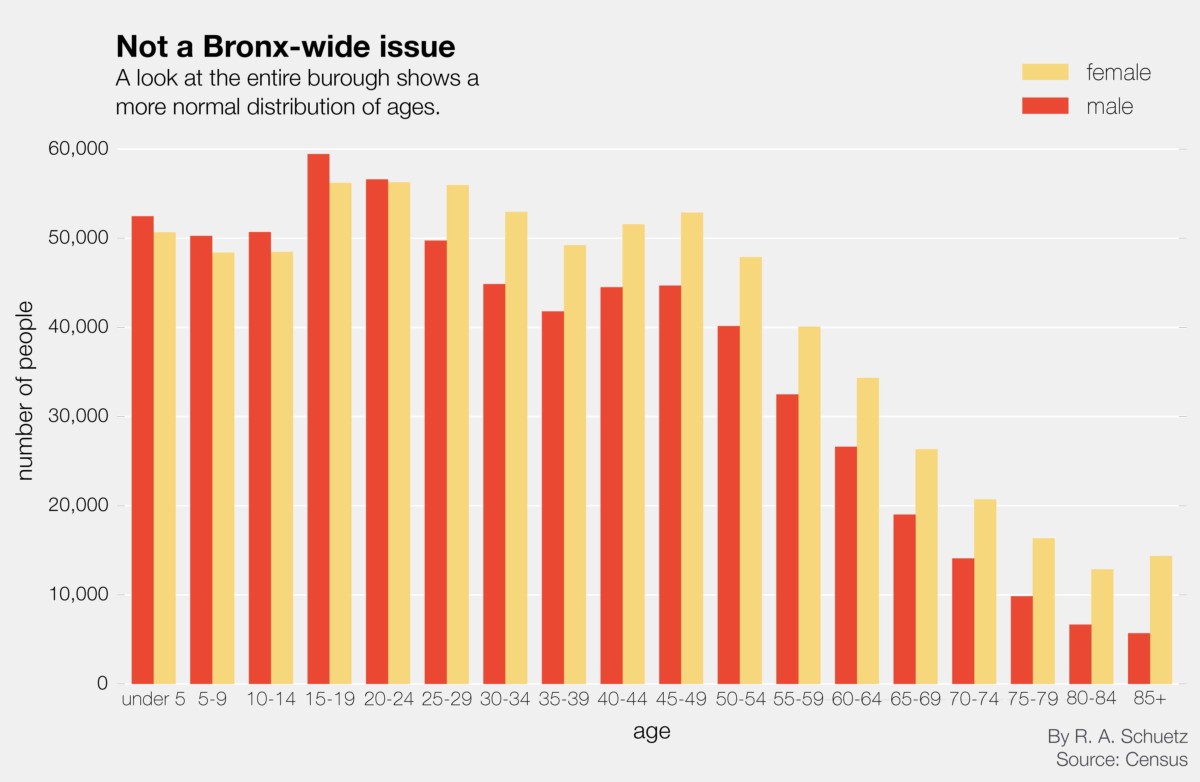

Which is a worrying figure, given that the number of young men living in the area was already disproportionately low. According to Census data, for every two male teenagers in the area, there is only one man in his late thirties. The problem is a stark example of a trend taking place throughout the Bronx, where for every three male teenagers, there are two men in their late thirties.

Census data shows that between 2005 and 2010, there was a 20 percent drop in the age bracket for men living in the neighborhood.

Michael Mincey, who first moved to the Edenwald Houses when he was 4, believed that men caught between the Scylla and Charybdis of gang activity and aggressive policing are facing particular pressures to move out of the area. “Honestly, if I were to have a kid with somebody, would I want to raise him here? No,” said Mincey, 36, an administrator at the East Bronx Academy for the Future. “I don’t want to worry about getting shot. And I don’t want to worry that, because I’m hanging outside with a friend that I know, I might get caught in a big sweep because the cops think we’re selling drugs.”

As a result, Mincey has been looking at apartments in the nearby Westchester town of New Rochelle. Many of his friends have moved out of the city and out of the state.

Michael Mincey and James Wallace both grew up in the Edenwald Houses.

“I look at males across the board as an endangered species,” said Brett Scudder, founder of a mental health intervention foundation in the neighborhood. “If they are in trouble, there are no safety nets. There are no safe environments.”

“They’re incarcerated,” said Jim Orekoya, a community center director in the Williamsbridge. In 2015, over 2,900 felonies and 5,900 misdemeanors took place in the precinct, according to police data. But he pointed out other contributing factors, such as immigration patterns and the job market.

“To have made it out of here is a great thing,” said James Wallace, a school paraprofessional who left the Edenwald Houses for Co-op City when he was 33. “You lose friends at an early age: death, drugs, prison. So it’s time for us to go.”

He had fond memories of growing up in at Edenwald. “We had fun,” he reminisced. The children in the building would play whatever sport was in season—basketball in the summer, football in the fall, and a bottle-top game called skelly in between. “We were all playing in the street. That’s how it was. Compared to now, when you hardly see anybody, but you hear about it in the news,” he said, alluding to violence he attributed to both gangs and police.

But violence wasn’t the only reason Wallace moved. He also felt the need to get away to have room to grow. When he first got a job, he remembered a change in his friends attitudes toward him. “When you come back around, everybody’s face is different,” he said, blowing out a stream of breath. “Little side comments and gestures. It’s like crabs in a barrel. Just because a man has a job, he’s not part of your clique anymore. You have to watch your back and be careful because you don’t know if they’re trying to do something to you. That’s the way of life around here.”