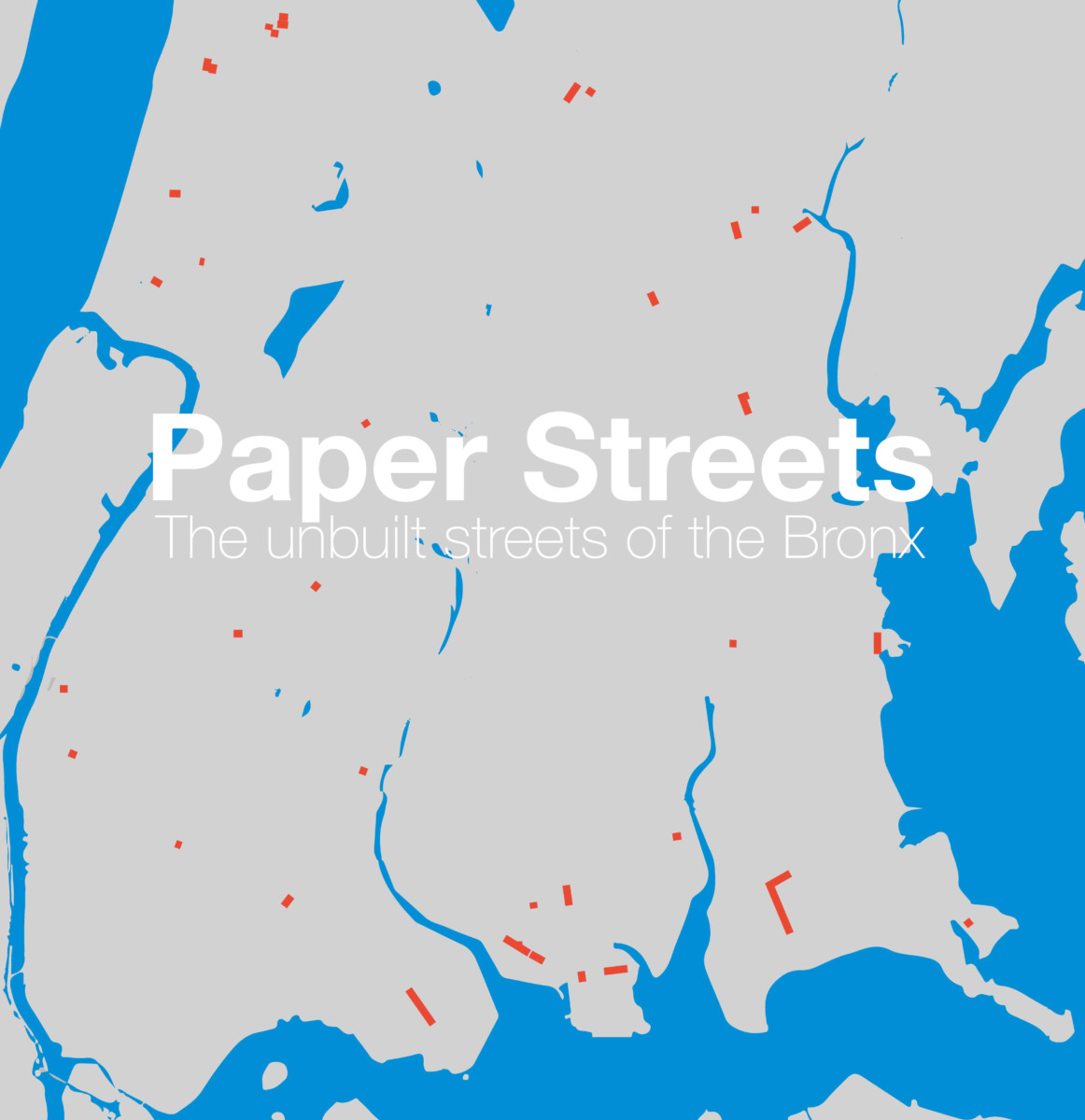

At least 40 streets around the Bronx have never been built.

On a typical Saturday morning in September, Denise Martin stepped out on the front steps of her Baychester home in the Bronx with a rake and gray gardening gloves. Shards of glass from a broken TV, an empty wine box and liquor bottles lined her front fence. To her right, the trail of garbage intensified alongside the shoulder-high tangle of weeds separating her house from a storage facility roughly 200 feet away.

Martin, a retired Verizon call center operator, said that all this was despite her efforts to clean the debris three to four times a week. “I know it’s a secluded block,” she said. “But people should understand—somebody lives here. If you see it’s clean, why would you eat your lunch and just dump it out? There are condoms over there. People poop over there. Anything you name is over there. Liquor, panties—oh, God.”

Martin believes the vacant lot next door to her house attracts all this trash. Despite her efforts over the last three years to get the city or the borough to tend to the overgrown lot, she has continually run into a brick wall. Or, rather, she’s run into a paper wall. It turns out that part of the patch of neglected wilderness next to her house isn’t technically a lot at all. It’s a street, at least on paper.

This stretch of land where Arnow Avenue should connect with Edson Avenue near Interstate 95 is one of at least 40 derelict lots that show up on city tax maps as streets. Community District 12 Manager George Torres called these unimproved stretches of land paper streets. “They show up on the tax map, but not in reality,” he said. “So if you didn’t know any better, you would think there was three acres of private forest in this area, nature reserve.”

To understand why that street was never built, you need to step back to when the surrounding land was first developed. When a new structure is built, the developers are responsible for building the bordering street and sidewalk. And according to a city Department of Transportation spokesperson, buildings that have not done so will not receive a Certificate of Occupancy, which allows that building to be used. The loophole is that buildings built before 1938 do not need a Certificate of Occupancy. And Torres said some developers were also able to waive their portions of the streets.

This has resulted in streets in varying states of limbo. On one portion of Ely Avenue, neat brick townhomes face an overgrown vacant lot; from the sidewalk bordering the homes, the pavement stretches halfway across the street before dissolving into the gravel that makes up the unbuilt half. A paper street adjacent to Seton Falls Park transitions seamlessly into the preserved natural land; two others in Throgs Neck have been manicured as part of Trump’s golf course overlooking Manhattan.

And on the other side of the Bronx, a paper street in Riverdale that nearby residents attempted to transform into an organic community farm is also in limbo. Michael Forman, a Bronx native who stumbled across the unused land in his neighborhood, had the vision of turning it into an organic flower garden. Like the paper street near Martin’s home, this section of 240th Street had also been used as an illegal dumping ground. He and his friends first had to clear the lot, carting off roughly 700 pounds of garbage by Forman’s estimation, and the items they unearthed gave testament for how long the land hand been forgotten. “We’ve found glass bottles of companies that don’t exist anymore,” said Forman. “We even found a rotary telephone.”

Forman applied for permission to use the land through GreenThumb part of the Parks Department which turns city-owned vacant lots into community gardens. But he said he worked with GreenThumb for a year and a half to no avail. “Since we’re a mapped street, GreenThumb cannot identify what city organization owns the land,” explained Forman. Since they could not find who owned the land, they could not request permission. Today, though Google Maps recognizes the swath of land as Pure Love Organic Farms and Forman has now been growing tulips, hyacinths, crocuses, and irises there for four years, the community garden does not officially exist.

In the meantime, no city agency seems to be willing to take responsibility for the growing garbage crisis. Last year, Martin said she caught three raccoons in her attic and paid nearly two thousand dollars to have the hole they tore in the roofing repaired. She’s upgraded to a sturdier trash can and sprays her yard weekly with Critter Ridder to ward off further invasions.

Denise Martin looked out through her fence toward the paper street.

Torres said that his office has heard complaints about paper streets nurturing much smaller critters as well. “With this whole Zika scare,” he said, “you have a lot of people saying these are breeding grounds for mosquitos.”

Another resident who lives next to an unconstructed part of Harper Avenue cited safety as a concern. “There should be a law against it, especially as it’s near the school,” said Rachel Hinton. She worries about walking past the forested street at night because it’s difficult to see the people who walk through it. According proposals for the Bronx Community Board budget, the street has been a budget priority since 1987. Another paper street between Boston Road and the New England Thruway has been a priority since 1994. However, neither request made it into the final budget.

Since paper streets, unlike lots, do not have owners, responsibility for these problems is unclear. The city Department of Buildings is responsible for ensuring that sidewalks and pavement are built with new developments; the Department of Transportation is responsible for maintaining streets, but neither oversees the building of streets for already existing buildings. Torres said the Department of Transportation had taken the stance that homeowners bordering a paper street should pave their own sidewalk plus half of the street, meeting one another halfway. But their spokesperson did not confirm such views. And Martin was unaware that the land bordering her house was a street in the first place.

Martin stood outside her home, which she has been trying to keep clear of garbage and wildlife.

“Well, for whatever reason, it wasn’t done,” said Torres. “These homes have been there for twenty-plus years. Who’s going to do it now?”

In the meantime, Martin took out her rake to begin tidying up her front yard. A garbage truck drove down her street, and she waved and yelled, “Good morning!” to no response. A sanitation worker loaded her tidily packaged garbage bag into the back, and the truck pulled off, leaving the wine box and glass bottles abutting the unbuilt street to someone else.