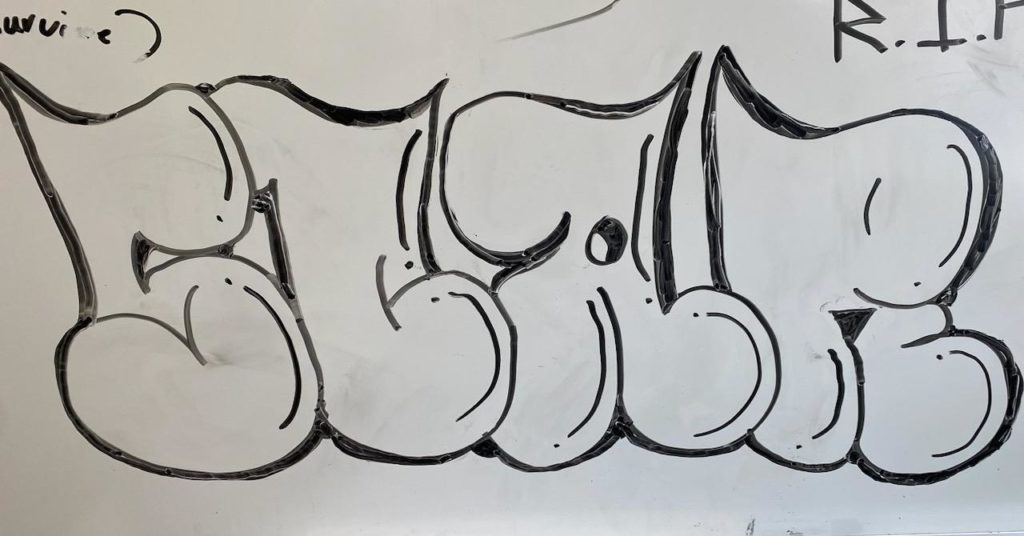

When asked about graffiti, eighth-grader Alexander Vazquez lights up. For him, painting is a way to escape dark thoughts.

“I used to be… not in my good side of my life. So I would do graffiti,” he said.

In a twist of fate, after Vazquez was caught painting graffiti in his school’s bathroom, the Bronx Community Charter school he attends is now allowing him to paint a mural on the roof.

It was a way the school could encourage Vazquez to find joy in coming to school, according to his art teacher, Kendra Sibley. This will give him a legal space to experiment, she said.

Vazquez’s is a unique case, as not all New York City schools afford children the opportunity to learn about or practice graffiti. Sibley estimates that roughly 40 percent of all art teachers incorporate graffiti, however, only 10 percent dedicate time to learning about different artists and their history.

“For me, it’s been less about ‘let’s all learn how to draw graffiti letters’… But more about ‘let’s learn about these artists’… ‘let’s learn about the history,’” Sibley said

Her efforts to examine the art beyond the surface, allow kids like Vazquez to explore their own roots as well.

“I wish I could do something that represents Mexico because that’s my country… I feel like (doing graffiti) is in my blood,” Vazquez said.

And in a neighborhood like the Bronx, graffiti’s history is significant.

“The Bronx is the mecca, a lot of people from different parts of the world come here to prove they can paint,” Sotero ‘Bg183’ Ortiz said. He is a member of Tats Cru, a Bronx-based group of professional muralists. The founders met during an art class in high school in the ‘80s and have been active ever since.

“What we paint becomes these kid’s Picasso, Monet, it’s the only art they see,” Hector ‘Nicer’ Nazario, another member of Tats Cru, said.

Sibley’s art curriculum acknowledges the colorful streets of the Bronx and incorporates street art and graffiti. For her, it is important that art is representative of her students.

However, Sibley’s freedom to incorporate street art and the opportunity that Vazquez has gotten, as a result, is not necessarily common. In the words of Vazquez, the Bronx Community Charter School is ‘a special school.’ Apart from its progressive approach, charter schools also operate differently from regular public schools.

Charter schools are founded by a not-for-profit board of trustees. They have a lot more autonomy when it comes to curriculums, grading, and academic missions.

According to the New York City Independent Budget Office, the schools are still publicly funded, which consists of per-pupil tuition funding, as well as additional funds, such as foundational grants, to cover the cost of ‘supplementary services.’ This means that they receive less public funding than traditional district schools.

As charter schools are independent public schools, budget cuts like the controversial one proposed by Mayor Eric Adams this year will not affect teachers like Sibley as much.

“I spend about $2,000 on the supplies for the art room. But then throughout the year, as we’re doing things and working on projects…. Nobody ever says no to me when I send an e-mail saying that I need [something]… It’s really crazy that it’s so nice that way here,” Sibley said.

Still, she voices concerns about what slashing $373 million might do to art programs in other schools.

“Because of lack of funding, I think materials end up being very limited and so people do a lot of drawing because it’s cheaper,” Sibley said.

In a 2019 roundtable survey, 67% of principals said that art funding is insufficient. Since then, the budget for the arts has decreased.

According to NYC’s comptroller, the cuts will affect 77% of all public schools and the Bronx is home to more than 100 of these schools. Apart from funding, the Department of Education provides principals with a guide for the arts, but the information is limited, making mention of the number of hours that art should be taught and that visual art, like drawing, is mandatory. The same department mentions including different cultures and local artists. However, this functions as a guide, not as a requirement.

The minimum art requirements eighth-grade students must complete were only met by 34% of students in New York City in the past school year. This rate is unaffected by the pandemic, as it has remained similar since 2016.

For Vazquez, the streets are his inspiration. Particularly, the art in the Yankee Stadium train station, which he pauses to look at on his way to therapy.

“I want to be just like them because it’s cool how you could just turn lines into something colorful and meaningful,” the thirteen-year-old said.

The roof of the Community Bronx Charter School is an open canvas, divided into different sides that are organized by color. While Vazquez’ plans for his mural are still in the making, he thinks his end product will feature learning blocks that children play with, together spelling out the word “blue”. And the mural is just the start; Vazquez has big plans for his future.

“My dream piece…is Godzilla holding my name,” he said.