A retired New York City marshal described a typical day of work like this:

It’s 27 degrees Fahrenheit outside, and there are four inches of snow on the ground. He knocks on the door of a low-income Bronx apartment. A woman answers. He tells her he’s a marshal. She’s being evicted for not paying rent. The woman starts to cry. Her three children, ages 2 through 7, gather in the hall.

Could you throw this family out on the street? If the answer is no, said Joel Shapiro, a city marshal for nearly three decades, then you should find another job.

It was a situation he found himself in often. “That’s why we’re the bad guy,” said Shapiro, casually, in a thick Bronx accent. “The average person cannot do this.”

Shapiro, 75, is a lifelong resident of the Bronx. For years, he made his living carrying out evictions—as many as 12 a day—across every borough of New York City. He came face-to-face with the city’s most vulnerable—the disabled, the undocumented immigrant, the single mother of three.

Marshals keep a busy schedule, with an average of more than 20,000 evictions carried out in New York City each year, and only 35 men and women specifically licensed by the city to perform them.

“Does it bother me? Yeah. Do I lose sleep over it? No. You have to block it out. If you know you can’t do it, you don’t take the badge. Simple as that,” said Shapiro. “It’s a job.”

A job that he’ll be the first to admit, “takes a weird personality,” to hold down. But a job, nonetheless.

Badge #57

Marshals don’t like talking to journalists, so both the position and those holding it are elusive by nature.

They’re the only player in the eviction process whose responsibilities take place outside the confines of the court proceedings.

“No active marshal will speak with you. Don’t even bother. Don’t even try,” said Shapiro, who sat outside on the concrete porch of his Throggs Neck home in the southeastern Bronx on a Wednesday afternoon.

“I can show you articles in every single magazine and newspaper, and they never come out right,” he said. “We always look bad, because we’re the bad guys. We know that. There’s never been a good article written about us.”

Over a three-day period in early October, steady calls to the offices of all 35 active marshals asking for interviews yielded nothing. On the other end of the phone were office managers, secretaries, some friendly, others not. Fancy answering machine menus offered various options like, “For eviction services, dial 1.”

Not a single active marshal responded for comment.

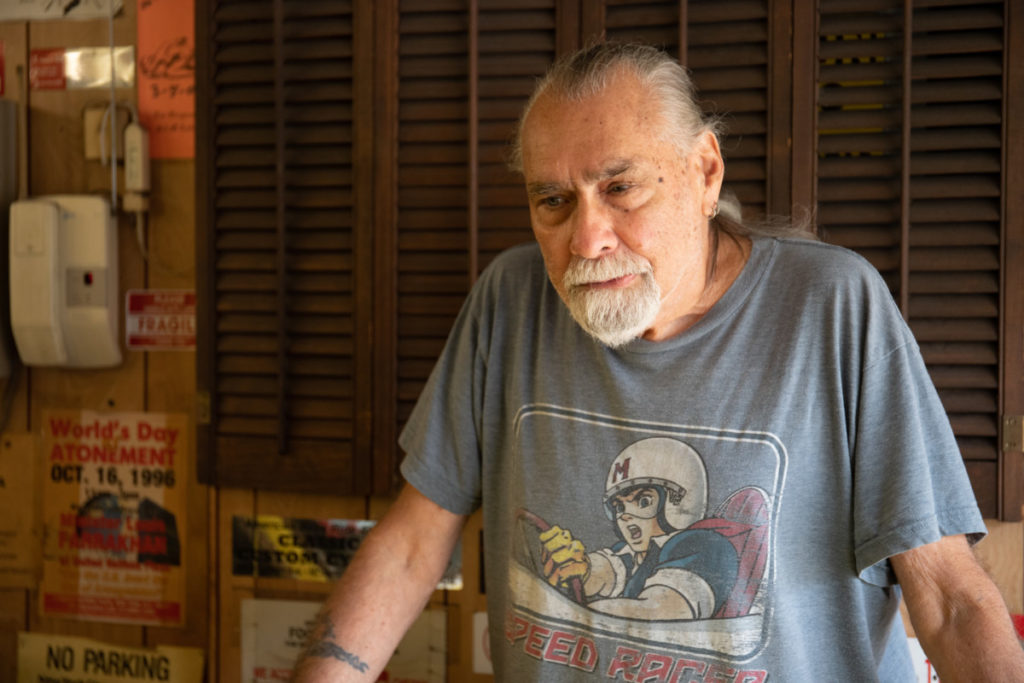

“The only reason that I would consider talking to you is that I’m retired,” Shapiro said. His gray hair was pulled back in a tight, shoulder-length ponytail. His feet outfitted with fuzzy house slippers were propped up on the wrought iron banister that lined the front of his house.

According to Shapiro, not much about the work has changed since he was first assigned his badge — Marshal’s Badge #57 — in 1982 by then-Mayor Edward Koch.

Although marshals are appointed by the mayor, they are not city employees.

“You can’t just (appoint) a marshal. The mayor has got to form a committee and then you go before the committee, and they decide whether or not they want you,” said Shapiro. “It’s basically a political appointment, but they can’t call it that.”

To apply, all potential candidates need is a high school diploma or a GED and to be at least 18 years old. But the appointment process is neither common nor simple. The paper application alone is 22 pages long, and appointments are extremely rare.

According to the NYC Department of Investigation, the department that oversees marshals, “no more than 83 city marshals shall be appointed by a mayor.”

But few mayors have come even close to reaching that number.

Mayor Bill de Blasio has only appointed one city marshal so far during his five years in office. Former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani didn’t appoint a single one.

“They see us as a liability,” said Shapiro. “You break into apartments and you carry a gun. Tell that to an insurance company, they want nothing to do with you. It’s not an easy job.”

To a certain degree, marshals share responsibilities with county sheriffs. Both can act as debt collectors, scofflaw and eviction enforcers. But sheriffs are employed by the city, earning a salary, benefits and a pension.

Marshals, on the other hand, are self-employed, and pay the city a percentage of their earnings in exchange for the right to do their job.

In 2018, the city collected a total of $1,908,480 from 35 marshals without spending a dime, according to data provided by the Department of Investigation. The payment is a requirement if a marshal wants to keep their badge, and costs $1,500 a year plus 4.5% of a marshal’s gross annual earnings.

“It’s free money for the city,” Shapiro said. “What you make depends on how many jobs you do.”

In 2018, 18 of the 35 marshals brought in more than $1 million a year, but that money doesn’t go directly into their pockets, said Shapiro.

“You have to pay your office girls, and for the office space. If you’re doing cars, you have to pay the tow trucks and for the lot you tow them to,” said Shapiro. “There are costs. You’re self-employed. You got to buy your own staples, just like everybody else.”

There’s more to the story

Tacked onto the walls of Shapiro’s garage are signs that tell the stories of some of the evictions he carried out over the course of his career.

On one side, there’s a sign for a birth control clinic. On another, a sign reads “Michelle Psychic Palm and Tarot Card Readings.” That one he said he took from the site of a job years ago.

Shapiro remembered telling the psychic, “Come on Michelle, you should have been expecting me.”

“I got stories that’d make you laugh your ass off,” he said.

Shapiro is not a big man, no more than 5-feet, 7-inches tall, with blue eyes, tanned skin and a short-trimmed white beard blanketing his face. Threaded through his left ear are two small, silver earrings. Cuffing his upper right forearm is a dark tattoo of his mother’s initials, one-half inch thick.

The neighborhood street where he lives is fringed with cars and single-family brick homes decorated with flowerpots and recycling bins and fall-themed gourd arrangements. He has a neighbor named Gina who drives a Volkswagen and sells organic face cream. A statue of a wood-carved squirrel sits at the edge of his driveway.

“What’d you expect? A monster?” he barked to a first-time visitor, scanning the middle-class residential scene.

The men and women who serve in the final act of New York City’s eviction machine have never had the best reputations.

Evictions begin with a missing payment, followed by a petition to appear in housing court, and end months, often years, later with a knock on the door from a guy like Shapiro.

Newspaper clippings going back to the 1960s brand the men and women who do the landlord’s dirty work as cruel, sadistic characters who lack empathy and are driven by greed, prompting headlines like “$4M-A-YEAR VULTURE IS REPO-ING THE REWARDS,” and, “City marshal cited as deadbeat slumlord.”

It’s a hard image to puncture, especially when none are willing to speak to the press.

Shapiro said that marshals work alone. They share only a title, and he can’t speak to how others conduct their business. But when one marshal does wrong, he complained, they’re all branded as criminals.

Still, when Joel Shapiro spoke on record, he shed some light on the person behind the badge.

Born in the Bronx in 1944, and raised along Arthur Avenue, Shapiro was a college student at Hunter College, now Lehman College, before being drafted to serve in Vietnam in the 60s.

“Back then all they needed was a warm body to hold a gun,” said Shapiro. “But I was a wild kid. It straightened me out.”

When he returned to the Bronx, he finished his degree at Lehman and took his first job at P.S. 86 in Kingsbridge Heights, as an elementary school teacher.

“I love kids,” said Shapiro. “That’s the only reason you go into teaching.”

While it may seem off-brand for a man who would later make a living booting people from their homes, Shapiro is the kind of guy who cares deeply about education; he cares about the multiple approaches one can take when teaching a child to shoot a basketball.

“I ran a movement education program. It’s a problem-solving approach,” said Shapiro. “There’s more than one way to throw a ball. The ‘command method’ says there’s only one, here’s how you do it. Movement education let’s the child figure it out.”

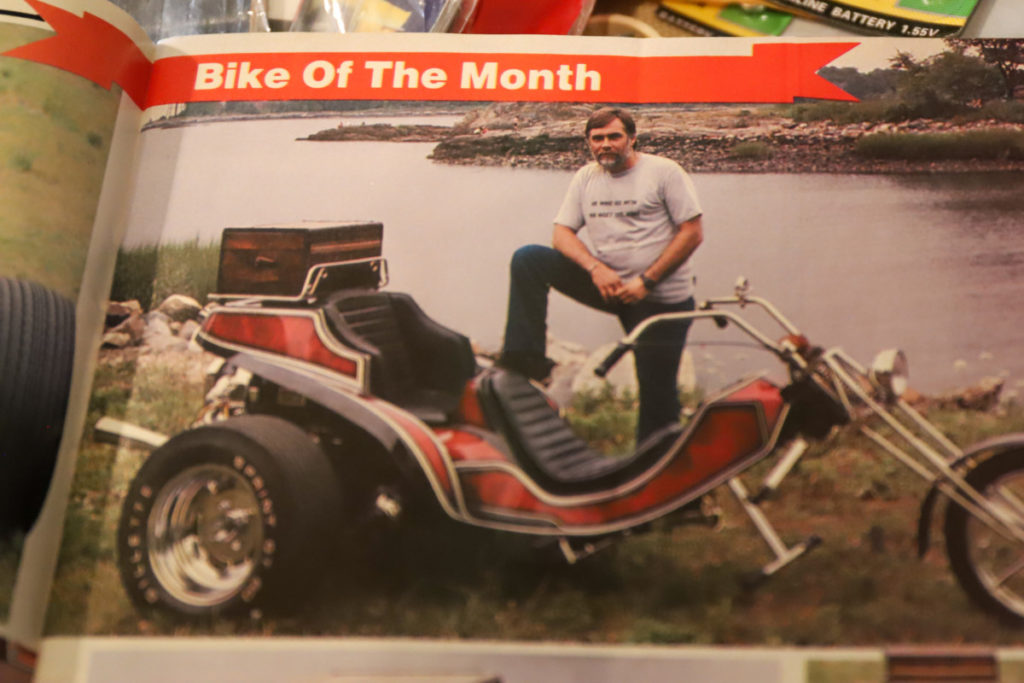

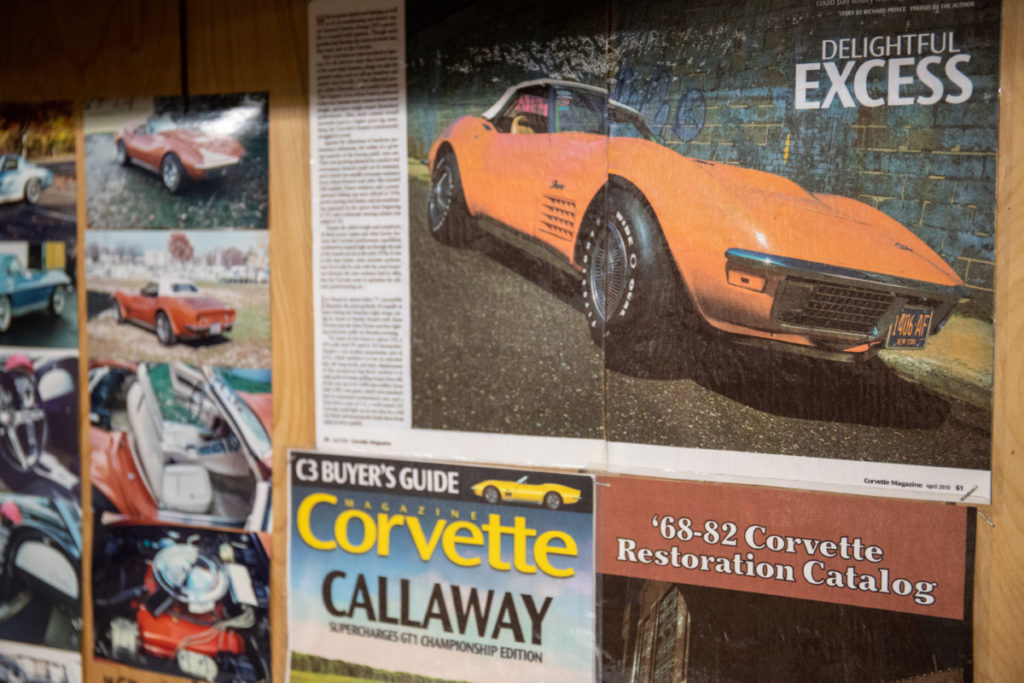

But when the city nearly went bankrupt in 1976, Shapiro said he lost his job. He began restoring antique cars to help pay the bills. It’s something he still does as a hobby from the garage of his home.

In the early 80s, when an opportunity came up to work as a city marshal, Shapiro said he took the leap.

“My father was a captain in the Bronx Court. He says, ‘Take a look at this, do you want to triple your salary in five years,’” said Shapiro. “So I quit teaching for good, and ended up taking the badge. That was it.”

The stories Shapiro tells about his time as a marshal range from funny and ironic, to tragic.

“You got to have the personality to deal with the tenant. Everybody has a different attitude, and it depends on why they’re getting evicted,” said Shapiro. “Some didn’t do their paperwork for welfare, others bought a house and decided they just weren’t going to pay their rent.”

He laughed when he recalled evicting Prince Egon von Fürstenberg from the Ansonia Hotel on the Upper West Side the same day he cleared out a crack house, and shrugged his shoulders when he recalled coming across three dead bodies during his 27-year career.

Only three. “Not bad,” he said, nonchalantly.

“I’ve walked into every situation you can imagine. You knock on the door, no one answers so you drill out the lock, and there’s a guy having sex with his girlfriend or wife in the bedroom. Didn’t even hear me break in,” said Shapiro. “I’ve walked into bad drug deals, I’ve walked into burglaries.”

“You name it, I’ve seen it,” Shapiro said.