The Bronx Hall of Justice where the Raise the Age Law means fewer and fewer 16- and 17-year-olds accused of felonies are prosecuted as adults.

Zachary Cassel, The Bronx Ink

On Oct. 2, Youth Part’s Judge Denis Boyle waited calmly from the bench in Bronx Criminal Court as attorneys, officers and aids busied themselves with preparations for the morning’s cases. All were gathered in Room 500 to decide the fate of the three teenagers on the docket.

It was the second day of the final phase of the 2017 law that raises the age of criminal responsibility to 18 in New York State. Starting Oct. 1, 17-year-olds arrested for felonies would now no longer automatically be treated as adults by the criminal justice system.

A prosecutor from the district attorney’s office in a grey and off-white suit readied at the desk among her colleagues. Yana Roy, a former Bronx prosecutor, sat on the front bench on the opposite side of the court reviewing her own case files, this time for the defense.

In the back row sat the accused, a tall, 17-year-old Bronx youth wearing a red Champions t-shirt and black sweatpants. He fidgeted next to Antoine Slater, his supervisor from the Youth Department of the Acacia Network, a nonprofit that focuses in part on youth rehabilitation.

The teenager, Neo C., stood accused of robbery in the second degree last November, when he was 16-years-old. His mother said that he’s been in court before, but for more minor crimes.

The previous year, Judge Boyle presided over the cases of 16-year-olds from the Bronx accused of crimes, moving all but a few of the most violent felony cases from adult court to Family Court. This fall, 17-year-olds now begin to fall under the same provision.

New York State was one of the last two states to halt automatically treating 16- and 17-year-olds accused of felonies as adults.

Before the 2017 Raise the Age law was passed, Neo would have ended up in Rikers Island correctional facility awaiting trial in adult court. But now, the Bronx teen stays at the Acacia Network, a nonprofit community service organization dedicated in part to troubled youth. Slater is his supervising youth worker.

Zachary Cassel, The Bronx Ink

According to the first annual report from the state on Raise the Age law, in the six-month period after October 2018, 16-year-olds arrested for felonies declined from an average of 244 to 155 per month, a reduction the report claims is due to “evidence-based interventions and services to address their needs.”

Felony arrests for 16-year-olds have been decreasing each year since 2013, according to a recent report from the Mayor’s office. In 2018, there was a record low of 1,915 felony arrests for 16-year-olds, down 11.3% from 2017.

Like Neo, these teens would have also ended up jailed with adults in Rikers Island had the state not raised the age of criminality to 18. The Rikers complex, known for a history of extreme violence, is slated to close for all prisoners by 2026.

Eileen Blake, Neo’s mother, rested her head on her arms on the back of the court room’s middle bench on Oct. 2. A fitness trainer by occupation, she wore green camo pants, her blue hair tied in a bun.

Attorney Roy and her client Neo assembled at one table in the courtroom, the prosecutors on the other. A court advocate between the groups was from The Fortune Society, an organization specializing in rehabilitation programs for the accused.

Now, because of the law, if Neo had committed a misdemeanor or non-violent felony, his case would be moved to Family Court.

“There are way more services for kids at Family Court,” said Deborah Rush, a juvenile attorney at the Bronx office of the Legal Aid Society.

Neo appeared before Judge Boyle because he is accused of a more serious crime, aggravated robbery. In New York, this means forcibly stealing property and harming an individual in the course of the theft.

Raise the Age created the adolescent offender category to refer to these 16- and 17-year-olds accused of felonies. For adolescent offenders, the legislation stipulates special holding facility requirements for children whom the judge determines need to be held before trial.

Acacia and Fortune Society are examples of accepted alternatives to being held with adults in Rikers.

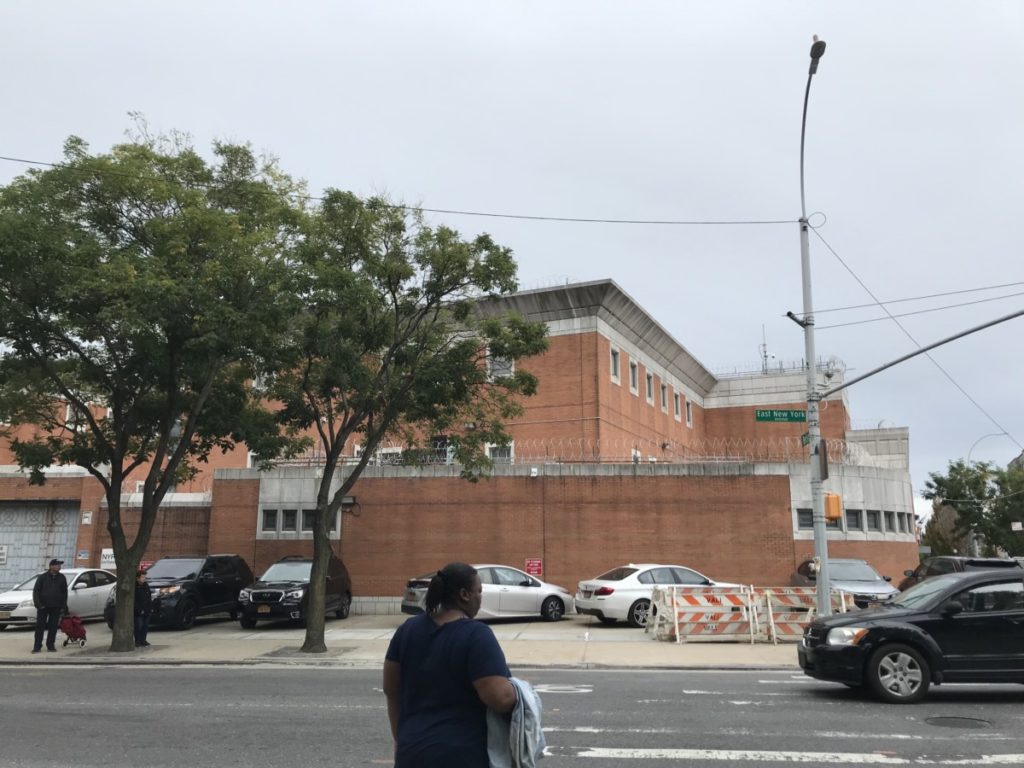

Crossroads Juvenile Center, the city’s second holding facility for children, located in Brownsville, Brooklyn.

Zachary Cassel, The Bronx Ink

By Oct. 1, 2018, all teens under 18 were transferred to Horizon Juvenile Center, a detention facility in Mott Haven in the South Bronx, according an Oct. 1, 2018, statement from the Mayor’s office. Seventeen-year-olds arrested before Oct. 1, 2019, would go to Horizon, while Crossroads in Brownsville, Brooklyn, would house those under 17, according to the statement.

Their crimes are also less likely to follow them through the rest of their lives. Teens who comply with the judge’s stipulations and work with prosecutors, may have their records sealed if their offenses are eligible. Several crimes are not eligible for a sealed record, including sex crimes.

Other categories under Raise the Age law include those who were 13- to 15-years-old when they were charged with a serious crime. Another exception are juvenile delinquents who committed misdemeanors either before they were 16, or were sent from adult criminal court to Family Court when they were 16 or 17 years old.

It is possible for the judge to move cases involving 16- and 17-year-olds to Family Court if they meet three criteria: the teen cannot have used a lethal weapon, caused serious physical harm, or have committed a sex crime.

In non-violent felonies, the District Attorney’s office can also block the case from entering Family Court if prosecutors prove “extraordinary circumstances” within 30 days, according to the 2018 Annual Report from the New York State Unified Court System.

Neo was 16 when he was arrested on the aggravated robbery charge. In the course of the robbery, a victim was injured. Because of this more serious charge, his case landed in the Youth Part of criminal court instead of Family Court.

The prosecution extended to Neo a guilty plea offer.

After discussion with his attorney, Neo accepted the offer. It meant that he would remain under supervision in the Acacia program. He would be required to remain substance-free, and stay on track to earn his GED diploma. If he complied and stayed out of trouble, he would be designated a youthful offender, which would mean all of his charges could potentially be removed from his record.

Neo’s supervisor at Acacia has been a youth worker at the organization for 19 years. Slater is currently responsible for over 40 kids ages 15 to 20, including Neo. The Bronx-based organization provides treatment based on the specific needs of the kids by creating one-on-one relationships between adults and teens.

“We specialize in behavior modification and substance abuse,” said Slater.

Part of his work includes ensuring kids wake up for school on time, attend their classes, and generally behave. Slater also provides counseling. He makes himself available to the kids if they’re having a tough time and need to talk to someone.

Slater is also charged with providing a report to Judge Boyle on Neo’s progress.

Judge Boyle brought up Slater’s report during sentencing, saying he was pleased to see that Neo was on track to get his GED, respectful of staff and other kids, and substance-free.

“You may be able to help your peers. This may be a real challenge for you,” said Judge Boyle, looking directly at Neo. “But I think you’re up to it.”

Slater thinks that Neo will be able to earn his GED and graduate from the Acacia program in nine to twelve months.

“One thing about him,” Slater said. “I think he’ll be successful.”

Neo stood beside his attorney with his arms wrapped behind his back as Judge Boyle addressed him. He shifted his weight from foot to foot.

His mother, Eileen Blake, said she wasn’t sure what she thought after they left the courtroom. A day later, she said that she still didn’t know why her son pleaded guilty. But, she added, she did respect the judge and is genuinely convinced that he wants children charged with a crime to be rehabilitated into society rather than locked up.

“I have no problem with him, because he’s always been fair,” she said. “I don’t believe [Judge Boyle] believes youth should be in jail.”

She and her ex-husband were fitness trainers, she said. Neo had an older brother. Growing up, Blake taught Neo how to play basketball.

When he was in the public school system, Neo started playing the trumpet. Blake said that he excelled. Six months after he started, he played in the Bronx Day Parade.

“He took the city,” she said.

A few things happened in his life that pushed her younger son in a different direction, Blake said. She and her husband split up and Neo’s older brother joined the military. Then Neo switched public schools into a smaller program that didn’t have the resources to allow him to continue playing the trumpet.

“The public school system took everything away from my son that made him shine,” she said.

In Nov. 2018, Neo was arrested for the robbery that brought him before Judge Boyle. According to state criminal justice statistics, between January and June, 2017 to 2019, violent felonies committed by 16-year-olds went down 15% in New York City as a whole, while in the Bronx they decreased by a third. It’s too soon to tell how rates for 17-year-olds may be affected.

In New York City as a whole, violent felonies have decreased by 5.4% for 16-year-olds. In the Bronx, they have decreased by 15%.

“There have been some coordination glitches with the city,” said Deborah Rush, a juvenile defense attorney at the Legal Aid Society in the Bronx, such as a van not reliably transporting teens to the Bronx Hall of Justice.

But on the whole, she says the implementation of Raise the Age has gone well.

Because of his good behavior at Acacia, Neo earned a home pass, which means he got to visit home for a day on Saturday, Oct. 5, according to his mother.

This would never have been possible if he had been held in Rikers.

“Neo has a cat that misses him desperately,” said Blake. “Blue-kai. That’s the one that picked him.”