In the Upper East Side on a chilly Sunday morning, every inch of the Asphalt Green Park is bustling with little soccer players wearing colorful knee socks and jerseys. Parents hold steaming cups of coffee and watch from the sidelines. Next door the basketball courts and playground are filled with children playing in the fresh air. But if the mayor’s waste management plan is carried out, up to 500 trucks transporting residential waste will pass directly through the park daily, disrupting this much- needed recreational space.

A 15-minute subway ride away, Barretto Point Park is a peaceful green oasis at the edge of industrial Hunts Point in the Bronx. It sits practically vacant except for a couple of kids skateboarding on the manicured paths and one man exercising on the basketball courts. In contrast to the Upper East Side, at least 15,000 trucks pass by Barretto Point Park every day, and when the air is still, the smell of sewage can become overwhelming.

Hunts Point in the South Bronx has been overburdened by waste for decades. The community has continually fought for green spaces, parks, and safe streets under the constant threat of industrial zoning and prolific waste management sites. The Upper East Side once housed a waste-processing center that eventually became obsolete. Residents there now face the threat of a new station, set to be one of the biggest in New York City.

While neither community wants the waste in their backyard, the city’s waste must go somewhere. And Mayor Michael Bloomberg says it is time for every borough to take on its fair share.

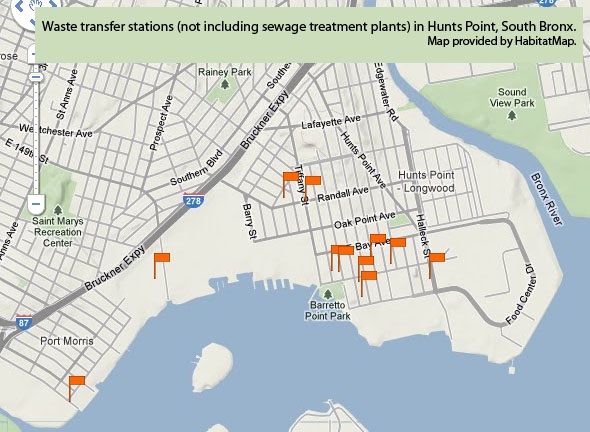

Every day, 33,000 tons of commercial and residential waste is generated in New York City. That waste is treated and transferred though 63 waste transfer stations and 15 of those stations are in the South Bronx, which handles over 31 percent of the city’s waste. Manhattan handles none.

The New York City Solid Waste Management Plan, presented by the mayor in 2006, aimed to distribute New York’s waste more fairly by introducing two new marine transfer stations in Manhattan.

One station is proposed at East 91st Street and the East River. The station will sit just a block from luxury housing, within 300 feet of a public housing complex, and next to the Asphalt Green in the Yorkville neighborhood of the Upper East Side, part of a congressional district with an annual per capita income of $85,081.

This marine transfer station would take up two acres, jutting 200 feet into the East River, and would handle all of the residential waste generated from 14th Street to 138th Street on the eastern half of Manhattan. Diesel trucks would transfer trash to the station on the river where it would be processed and shipped by barge to disposal sites outside of the city. While the station would help to distribute trash burden in New York City, it is hard to ignore how close this station would be to a very vibrant park.

While the city’s plan was a major victory for environmental justice groups and residents of the South Bronx, people living near the waste transfer site on East 91st Street in Manhattan are strongly opposed to what they see as a major encroachment on their residential neighborhood.

Residents for Sane Trash Solutions is a 12-member group fighting to stop the construction of the marine transfer station. The group says that spending $125 million to build a waste station near a park and public housing makes no sense. “There has to be a better solution,” said Jennifer Ratner, a group member and pediatrician who lives eight blocks from the site. “Our children are playing just an arm’s length away from what would become major truck traffic.”

The Department of Sanitation says that the new facility will be state of the art. Waste will be processed and shipped in new containers and the surrounding community will not be burdened with smell. But Ratner is skeptical. “Sure the facility might be state of the art,” she said. “But the diesel trucks carrying the waste through our neighborhoods will not be.”

Asphalt Green, which would be cut in half by a commercial truck ramp, is not a typical public park. In fact, 70 percent of park time is available only for those who pay a monthly $99 dollar membership fee, which also includes use of the indoor gym. In a lawsuit filed last summer against the city, residents attempted to halt construction of the waste transfer station by invoking the public trust doctrine that protects parklands.

The court favored New York City, finding that Asphalt Green was not a park and that the construction of the waste transfer would not significantly intrude upon the green space.

But while Asphalt Green is a fee-based non-profit organization, it does allow certain groups, like schools from East Harlem, to use the park daily for free.

And from the looks of it, by most people’s standards, Asphalt Green is a park. “You can bring a 4-year-old here and ask them what they are seeing,” said Ratner. “ I guarantee you, that child will say they are looking at a park.”

With lawyers, lobbying efforts and community-based actions, the group continues its work to halt the mayor’s plan.

It’s also not clear whether the transfer station at East 91st Street would actually provide some relief to the South Bronx, a community with an annual per capita income of $13,959, making it the poorest congressional district in the United States.

“If the efforts of groups on the Upper East Side are successful it would mean, at the very least, the commercial waste that’s generated on the Upper East Side will continue to be trucked to the Bronx,” said Eddie Bautista of the Environmental Justice Alliance.

Sandra Christie, a resident of Yorkville and member of Sane Trash, disagreed. She claimed that that the proposed waste transfer station in the Upper East Side will in no way affect the South Bronx. “Not a speck of the trash that will be processed at the proposed station currently goes to the South Bronx,” she said. “I feel for the people living there, but this station will not solve their problems.”

But mixed messages may be coming from within Residents for Sane Trash Solutions. A recent article in the Daily News quotes the president of the group, Jed Garfield, suggesting the city “put the facility near the Hunts Point in the South Bronx where it would not actually touch any neighborhoods except the Hunts Point Market.”

The problem is, people actually do live in Hunts Point, and many residents currently live near waste transfer stations.

People that have grown up in Hunts Point consider the smell of sewage and trash a fact of life. Wanda Salaman, of the non-profit organization Mothers on the Move, has been fighting the smell for 10 years.

She knew things had really become unbearable when a reporter covering her fight against trash told her that on the subway back into Manhattan from the South Bronx, people on that train began to hold their noses. “It was then the woman realized,” Salaman said. “The smell was coming from her.”

Mothers on the Move’s first fight against sewage in Hunts Point targeted the New York Organic Fertilizer Company, a company that converted human waste into fertilizer pellets. The smell was so bad that families living near the plant at Barretto Point Park had to keep their windows closed during the summer.

After a decade of fighting, they succeeded when the city cut its contracts with the sewage treatment plant, and the company was shut down. But the Hunts Point Sewage Treatment Facility, another sewage processing company, still remains.

“The smell has gotten better in the last few years,” said Jahira Rodriguez, who grew up in Hunts Point. “But in the summer, it is still really bad.” Rodriquez thinks it is unfair that the Upper East Side is refusing to process their fair share of garbage.

In addition to the thick smell of sewage in the South Bronx, waste transfer through the neighborhood also contributes to high asthma rates. According to the Department of Public Health, Hunts Point has one of the city’s highest asthma rates for youth ages 0-14 at 11.5 percent while The Upper East Side has on of the lowest at 1.2 percent.

In 2006, researchers from the New York University Graduate School of Public Service found that high asthma rates in the South Bronx are directly related to the multitude of trucks that pass through the neighborhood daily. Many of those trucks are carrying commercial waste from other boroughs to the waste transfer stations in the Bronx. The mayor’s plan aims to alleviate truck traffic allowing the majority of waste to be transported by barge.

Truck ramp next to the Asphalt Green in the Upper East Side where trucks will carry waste to the proposed marine transfer station. (JANET UPADHYE/Bronk Ink)

Mouloukou Diakite, 48, exercises at Barretto Point Park, the closest green space to his apartment in Longwood. His daily routine includes running laps around the basketball court, breathing through push-ups against a steel fence and jogging backward in the grass. Unfortunately his son Mory, 13, is unable to exercise with the same intensity because he has asthma.

Mory had trouble breathing at a very young age but was lucky to have never been hospitalized because of his asthma. He was also lucky to spend some time in his father’s home country of Mauritania where his asthma cleared up enough for him to now play basketball on his school’s team and sometimes join his father at Barretto Point Park. In order to get to the park from their Longwood apartment, the Diakites must pass through streets zoned for industry.

The city’s zoning policies are another example of the burden placed on Hunts Point. A large portion of the neighborhood, 41.3 percent, is zoned for industry and commercial use while only 3.1 percent of the Upper East Side has been zoned for the same use. The proposed waste transfer station will be built on that land. In a small geographic area where there is a high concentration of residents, such as New York City, people are forced to live and play near industrial zones.

The Tri-State Transfer Station in Hunts Point, which handles 84,836 tons of material annually, sits just three blocks from a tree-lined street of single-family homes and a Head Start program. Two blocks from the station is the first of several six-story apartment buildings, each with a minimum of 60 apartments. One block from the plant is Dancers Dreamzzz dance studio where local youth can take salsa, hip-hop or ballet classes. As kids break from class, they step outside to breathe fresh air and can see a waste transfer station.

Sharon De La Cruz, 25, grew up in Hunts Point. She is used to the smell, air pollution, and high asthma rates that accompany heavy industry and waste processing. For her, it is a normal way of life, but that doesn’t make it fair.

“I am sorry that a waste transfer station is proposed near a park in the Upper East Side,” she said. “But in my neighborhood, we have the opposite problem. We have to propose parks in the middle of several waste transfer stations because that is the only land we have.”

De La Cruz loves Barretto Point Park but says that it is difficult to walk past waste treatment plants and a line of diesel trucks to get there. She thinks that the trucks and the odor keep people out of the park. “Don’t we deserve accessible green spaces too?” she asked.

Bautista believes that they do. Industrial or not, people live their lives in Hunts Point. “Residents for Sane Trash Solutions justify suggesting the Bronx and our other communities of color because they’re industrial,” said Bautista. “They ignore the fact that we have a few hundred thousand residents living in these communities as well.”

While the Upper East Side fights the mayor’s plan, residents of the South Bronx wait and wonder when the burdens of air pollution and smell will lessen in their small community. “We don’t want to be the community that takes on everyone else’s trash anymore,” said De La Cruz. “It makes us feel like we are trash.”