It’s an intersection like many others in the Longwood section of the Bronx: a large field of fractured asphalt with road markings in fading yellow and white, old brick buildings with fire escapes and the subway running on its metal stilts somewhere in the far background. Only the green northern tip of Rainey Park distinguishes the intersection of Intervale Avenue and Dawson Street. But soon it will be also known as Arsenio Rodriguez Way, named after a Cuban bandleader who died in 1970 and whom many consider a major figure in the evolution of salsa.

“Hopefully, the new name will be up later in October,” said Jose Rafael Mendez Jr., the Latin music fan who is behind the effort to rename the intersection. “But maybe it will be November. Let’s hope at least before the end of the year.”

Mendez has long fought for honoring one of his favorite artists. He first presented his idea to the Community Board 2 in Longwood on April 11, but not all of the members were there. He gave the same speech in May and finally convinced the board, which passed his request on to the City Council, where it was approved on Sept. 25. Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed the necessary papers on October 2.

The intersection between Intervale Avenue and Dawson Street is scheduled to be renamed Arsenio Rodriguez Way. (JAN HENDRIK HINZEL/The Bronx Ink)

But Mendez’s quest really began much earlier, in 2005, when he overheard a friend who had just moved to Westchester County say that he was living near the cemetery where Arsenio Rodriguez was buried. Mendez, who is from Tarrytown in Westchester County, soon found out that it was Ferncliff Cemetery –the same cemetery where he used to walk with his girlfriend when he was a teenager. But when he was young, he didn’t know much more about Arsenio Rodriguez than the name. He didn’t know Rodriquez was buried there. There was no sign, no plaque, no other hint.

Mendez wanted to change that. Together with his friends Henry Medina, a film archivist, musician Larry Harlow, and journalist Aurora Flores, he helped to place articles last year in The New York Times and The New York Daily News telling the story of the anonymous grave. Then, something happened that Mendez didn’t expect. Rodriguez’s heirs contacted him. The musician’s wife had two children from a different marriage who now live Manhattan and the Dominican Republic. When she died, these stepchildren had the rights to the grave. Once the contact was established, Mendez asked them for permission to name the burial site and Larry Harlow bought a bronze plaque that now adorns the grass-covered grave.

But the three fans did not want to stop with the grave. The renaming of a street was up next. On their search for the right place they ended up at Playground 52, where they found Al Quinones, who works as a volunteer steward there. Quinones is always up for a chat about the Bronx and its artists. He knows where they all lived. At the playground, wall murals feature artists and people influential in the community. Quinones is all for giving them the fame they deserve. He named the little community garden next to the playground after William “Bill” Rainey, a Bronx activist. Quinones also has experience in getting projects going. Together with other community members, he has invested thousands of hours renovating the playground and fighting to renovate the old brick houses around it. “So many great artists grew up here and went to this playground,” Quinones said. He assured Mendez that he would support the new initiative.

Mendez felt that Rodriguez had been ignored in the borough. “Tito Puente had a street named after him six months after his death,” he said. “La Lupe has her own street in the Bronx. All these other Latin artists have places named after them. Why not Arsenio? He founded modern salsa. And isn’t the Bronx proclaiming itself the neighborhood of salsa?”

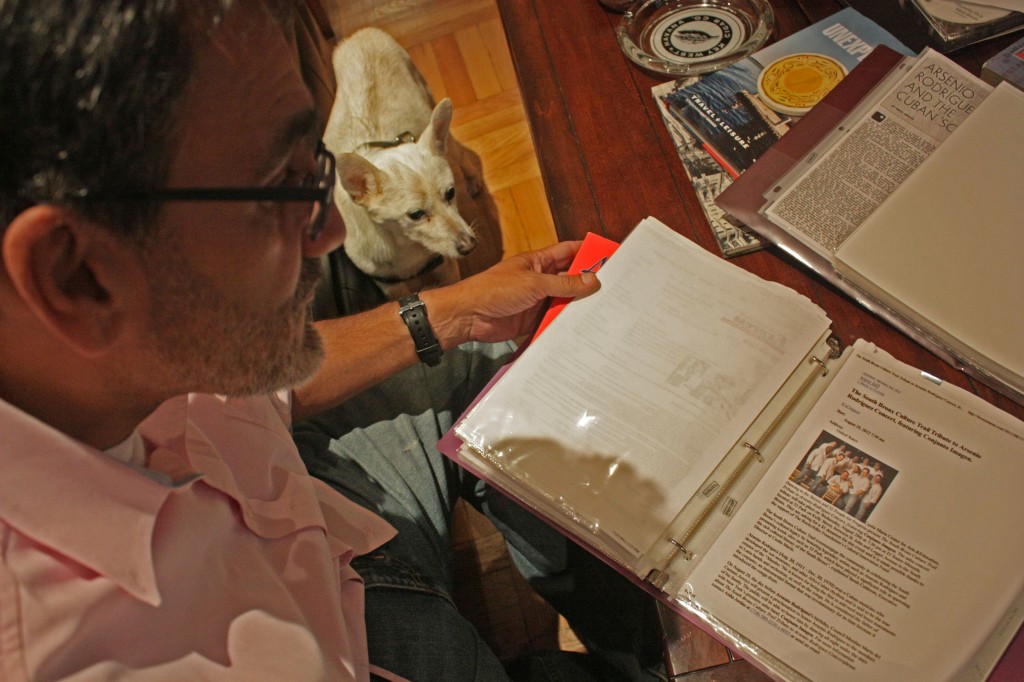

The 57-year-old New Yorker of Puerto Rican descent is a Rodriguez fan turned expert. His apartment on the Upper East Side looks like a music library. On the walls are posters and paintings of musicians playing guitars and drums. Folders, files, CDs and pictures with information about Rodriguez’s life fill his drawers and flood his living room table. When Mendez starts speaking about Rodriguez’s life, he doesn’t stop. He explains that Rodriguez was born in Cuba in 1911 as a descendant of Congolese slaves and grew up listening to African songs.

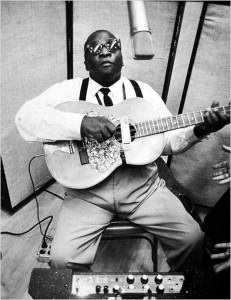

In the 1930s, performing with bands in pre-revolutionary Cuba, Rodriguez merged African and Cuban rhythms. His instrument was the tres, a guitar with only three sets of three strings as opposed to six on a standard guitar. All these sounds, Mendez says, became major components of the style of music called salsa.

Aside from the music, there is a special detail that connects Mendez with Rodriguez. Rodriguez went blind after he got hit by a horse as a kid. Mendez’s father lost his eyesight 20 years ago. “I feel like I can relate,” Mendez said. “His music resonates inside me.”

Mendez lowers his voice when he admits that Rodriguez also lived in Los Angeles, but raises his voice again to emphasize that his idol lived in the Hunts Point and Longwood sections of the Bronx for many years. He performed in places whose names are just memories now: Club Cubano in Prospect Avenue, Club Tropicana in Westchester Avenue or Hunts Point Palace, whose big corner building on Southern Boulevard today hosts a Duane Reade.

In all these places, Cubans and Puerto Ricans once celebrated Latin music together. But it took the Puerto Ricans to start the initiative to honor Rodriguez.

Mendez hesitates when he talks about the reasons for that. “Only rumors,” he said. There was talk about Rodriguez not choosing sides during the Cuban Revolution like many exiled Cubans, talk about Rodriguez being black and many Cubans in the Bronx being white. But he doesn’t want to make too big of a deal out of it. “In the end it doesn’t matter who did what and what not,” he said. “It’s not about being Puerto Rican versus being Cuban. We’re all Latinos. Arsenio symbolized that mixture with his music and his personality. He hired many Puerto Ricans in his band. But there were also black Cubans and black Venezuelans. This is about great music and honoring it.”

David Garcia, a musicologist, salsa expert and professor at the department of music at University of North Carolina, is also cautious when talking about racial issues in salsa. He sees a simpler explanation: “Puerto Ricans were just one of the biggest Latino groups in the South Bronx of the ’70s. They grew up with Rodriguez’s music. Of course there are more people of that group that could value his cultural contributions.”

Rafael Mendez archived every step of his initiative to rename the street. (JAN HENDRIK HINZEL/The Bronx Ink)

In Mendez’s folders, there are maps of various South Bronx neighborhoods. Using a yellow marker, he has drawn lines in them with anchor points that represent important stages in Rodriguez’s life. One of those points is Kelly Street, where Rodriguez lived; another is a location where he used to perform. Still another one is a temporary home. The lines cross at the intersection of Intervale Avenue and Dawson Street,” Mendez said. “This is the center of his life in the Bronx,” and the intersection that will be renamed.

The intersection was supposed to be renamed on Aug. 29: Mendez and the other Rodriguez fans gathered to celebrate the musician’s 101st birthday 42 years after his death. They even flew in from Cuba Rodriguez’s daughter by an earlier marriage, Regla Maria Travieso Montessini. Mendez had tracked her down.

But the re-naming had to be postponed because the city hadn’t yet given official permission. “Well, the mills of government are slow,” Mendez said. But he is patient.

“I’m that kind of research guy,” Mendez said. “A shy guy, the guy in the background. But on this initiative, I had to run at the front.” He seems still upset that Rodriguez’s musical achievements haven’t been acknowledged. “Rodriguez even dedicated a song to the Bronx: La gente del Bronx, which translates to people of the Bronx.”

Bobby Sanabria practices Latin music with his students at the Manhattan School of Music. (JAN HENDRIK HINZEL/The Bronx Ink)

Indeed, Rodriguez’s influence continues today. Bobby Sanabria, who also supports the street renaming, rehearses in a studio at the Manhattan School of Music in Morningside Heights, where he plays Afro-Cuban jazz pieces with students. “There aren’t too many young people into this sort of music,” said the multiple Latin-Grammy nominee. “They’re more into hip hop.” But he says Rodriguez’s legacy is everywhere in modern Latin music. “Arsenio Rodriguez has the same importance in salsa that Louis Armstrong has in jazz,” he said.

Many jazz teachers have their students listen to Armstrong. It’s the same for Rodriguez and Cuban music, explains musicologist David Garcia. Rodriguez did more than just set the path for the development of salsa, Garcia said. Rodriquez defined the trumpet play for modern salsa and was famous for his specific style using conga and bongo drums. Yet, modern salsa did not evolve out of Rodriquez’s achievements alone, Garcia said. “In music you can rarely give credit to one musician,” he said. “It all develops and emerges constantly. Often it is a collection of musicians of the same culture or area.”

That collaboration is also Rodriguez’s legacy. After a recent rehearsal with his students, Sanabria sat in his car listening to his own latest album “multiverse.” The first piece has parts of Rodriguez’s music, accompanied by Bronx rap artist La Bruja. He remained parked at the side of Broadway, turning up the volume. When the song was over, he started the engine, and drove back to his Bronx home.

The rhythms of salsa resonate in the Bronx, Mendez said. Salsa means home.

“Whether we are in Puerto Rico or here, we listen to the same stuff.” But the Bronx, he thinks, is a special place. “There is something about the people here,” he said. “They may not know how to pronounce artistic concepts, they may not know how to explain things. But they feel culture. They eat culture.”