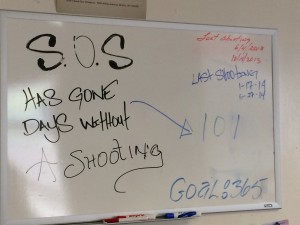

The whiteboard at the SOS South Bronx office displays the number of days since the last shooting in the territory SOS covers. (LAUREN FOSTER/The Bronx Ink)

It’s hard to hold your breath for 108 days.

At Save Our Streets South Bronx, which launched in January 2013, a whiteboard in their Mott Haven office read “107” on Oct. 13 and “108” on Oct. 14. They dread when that tally of days without a shooting in their 20-block territory must go back to zero.

Save Our Streets, or simply SOS, originated in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn in 2009 and has since expanded to 15 sites across the city. The City Council along with the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation, the largest U.S. charity devoted to public health, have pumped millions of dollars into this unconventional anti-violence initiative modeled after Chicago’s CeaseFire program. Now called Cure Violence, the program was celebrated in the award-winning 2011 documentary “The Interrupters.” Cure Violence has been emulated in roughly 50 cities worldwide since its inception 15 years ago.

The cornerstone of Cure Violence is the work of “violence interrupters,” “credible messengers” and “outreach workers” who patrol the streets and nurture relationships with at-risk individuals, typically young people, in an effort to undo a culture of violence of which they themselves were once byproducts. A job flier for SOS South Bronx (they’re hiring) describes such responsibilities for violence interrupters as identifying youth who are gang members or at-risk for joining, finding tips on potential conflicts, mediating with those parties involved to prevent retaliations and diffusing “hot spots” where shootings are likely to occur.

The credibility of these paid staffers is rooted in empathy.

“What I like about Save Our Streets is it’s composed of staff and volunteers who are former gang members or drug abusers themselves, or people who have been incarcerated,” said City Councilmember Vanessa Gibson, a Democrat who represents neighborhoods such as Morrisania and Melrose. “The best person you can get to really understand what a young person is going through is someone who has been in that situation before.”

Gibson allocated $5,000 of her discretionary funds for the 2015 fiscal year to SOS South Bronx. Democrat Robert Cornegy of Bedford-Stuyvesant and northern Crown Heights set aside $9,000. The Council voted earlier this year to expand SOS efforts from three neighborhoods to 15, including new posts in the 44th, 46th and 47th precincts in the South Bronx.

Jeffrey A. Butts, director of the Research and Evaluation Center at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, echoed Gibson’s assertion that knowing the streets is key for SOS employees. “They have to have some connection to the community that doesn’t make them seem like an outside meddler or do-gooder,” explained Butts. Researchers at his school are currently evaluating the Cure Violence model and its implementation in Crown Heights and the South Bronx. “Some of the programs have successful employees who’ve never been arrested, but they might be the son of a well-known gang leader,” he said.

SOS is guarded about disclosing details on its organization. An SOS staffer said the program’s parent organization, the Center for Court Innovation, clamped down on news media access after The Mott Haven Herald published the criminal record of an SOS interrupter. Robert Wolf, director of communications for the Center for Court Innovation, denied that claim but said “everyone is tied up here” and would be unavailable for interviews indefinitely. SOS staffers have been instructed not to participate in interviews without approval from the Center’s Midtown Manhattan office.

Butts, whose center at John Jay received more than $1 million from the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation and $750,000 from the city council to study Save Our Streets through 2016 in conjunction with the Center for Court Innovation, explained the concern over public scrutiny.

“These programs do get very skittish. There have been lots of stories about some of the dominant political infrastructure forces running to the media to explode the situation when something goes wrong,” Butts said.

“Cure violence does not conform with the dominant political culture surrounding public safety,” he added. “So when you’re talking about crime and violence in a public policy arena, people immediately think of policing, prosecution and punishment. This program does not fit that model, so you start off with immediate opposition from the people who think conventionally about public safety.”

In the South Bronx, SOS outreach workers are unarmed and identifiable by their red T-shirts. Although sanctioned by the city, they operate in communities where cooperating with police work is a serious taboo. Despite often being privy to criminal activity, SOS explicitly refuses to have contact with police.

“You have a disconnect with a lot of young people who don’t trust the police and don’t think police are there to serve the public and to protect them,” Councilmember Gibson said.

This wall of separation between law enforcement and social workers is not unusual.

“I was visiting some police departments in Washington, D.C., and they said they keep in touch with outreach workers at these types of programs, but only at the highest level,” Butts said. “They might hear, ‘Things are really heating up in this neighborhood’ or ‘We’re getting rumors that something is about to go down between this crew and that crew,’ but no individual names, no tip-offs and certainly no post-incident information to help the investigation find a perpetrator. As soon as you do that, word gets out and the whole program is dead.”

SOS South Bronx employs three interrupters and three outreach workers, all middle-aged, to engage a territory composed of four public housing complexes and about 20,000 residents. They work full-time Tuesday through Saturday, with shifts running as late as 2 a.m.

In Crown Heights, interrupters underwent 40 hours of training in direct consultation with Cure Violence experts in Chicago, according to a 2011 report from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance. SOS South Bronx is also in frequent contact with Chicago, allowing for a uniform implementation of the model.

Crown Heights had a homicide rate for those aged 15 to 24 nearly four times the city average in 2011, at 41.9 homicides for every 100,000 people in that age bracket, according to a report by the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. (The department is now an advisor to SOS.) Fordham / Bronx Park and High Bridge / Morrisania in the South Bronx were also in the top-five neighborhoods most plagued by youth gun violence. Whereas SOS Crown Heights developed a successful “Youth SOS” program driven by student volunteers, efforts to duplicate that youth engagement in the South Bronx have foundered.

“The youth are disempowered and basically have no opportunity. One of biggest frustrations from a social work perspective is when you’re not addressing the core causes behind these issues,” said Markus Redding, a professor at the Columbia University School of Social Work who has worked extensively in non-violent conflict resolution. “It’s going to be very similar to what we do in the court system, which is reacting to what’s there but not getting at root causes like better education.”

The Crown Heights program reported recruiting 96 community members between January 2010 and May 2012 to participate in the SOS mission. All but one of these recruits was male, 94 were black and two were Hispanic. An SOS South Bronx official said his team has fostered about 25 such relationships.

Researchers led by Butts have interviewed roughly 200 people about gun violence in neighborhoods with and without SOS programs, and they are analyzing shooting data in these test and control areas. Butts would not give any tentative findings — their work began in February 2014 and will conclude around August 2016 — but he did outline basic variables that impact Cure Violence:

“To what extent are public institutions well-coordinated? Do social services people talk to the schools? Do law enforcement know their own community? How do neighborhood residents feel about their access to necessary support? Are police seen as an outside occupying force?”

The SOS South Bronx office displays posters advocating ending gun violence. (LAUREN FOSTER/The Bronx Ink)

SOS South Bronx has struggled to form alliances with institutions in the area. An exception is the Bronx Christian Fellowship, a church in Mott Haven where Rev. Que English has collaborated closely with SOS efforts. English reiterated the need to solve violence through means outside law enforcement.

“There’s an idea in these communities that if a cop kills us they’ll get away with it,” she said. “It’s circulated throughout generations. I once heard a 5-year-old say, “I don’t like cops.’”

Religious figures are a core component of the SOS strategy, according to literature distributed at the program’s Mott Haven office. One form reads, “Faith-based leaders are encouraged to preach against gun violence from their pulpits.”

What would it take for programs such as SOS to thrive in the pastor’s community?

“My first thought is a miracle,” English responded. “If we had a wish list, it would be ongoing community awareness and a lot of media coverage because we need to get the word out on violence to turn the tide.

“It’s going to take a while, and there’s no quick answer,” she added.

Anti-violence initiatives are not new in New York City. In 1979, Curtis Sliwa founded the Guardian Angels, whose red berets and jackets became trademarks of the amateur pseudo-police force that patrolled the subway amid a rash of violence. That operation was controversial for its vigilante approach, instructing volunteers to make citizens arrests and even providing them training in martial arts. The Guardian Angels do not accept volunteers with gang affiliations or serious criminal records.

But Redding and Gibson support the inclusion of ex-convicts in SOS South Bronx.

“With the prison industrial complex — we have more people incarcerated in the United States than any other country in the history of the world — there’s such labeling and the stereotyping of anyone who has committed a crime,” Redding said. “That lack of a second chance is very frustrating.”

In areas of Chicago where Cure Violence has been implemented, shootings are down 75 percent, according to cureviolenge.org. Crown Heights saw a 6 percent drop in shootings from January 2011 to May 2012 — the first year and a half of SOS activity — while comparable Brooklyn neighborhoods saw increases of 18 to 28 percent in that period. Experts say it is premature to conclude a cause-and-effect relationship between SOS efforts and diminished shooting rates, but they point to these data as cause for optimism about the efficacy of Cure Violence.

Still, Chicago is far from eradicating its gun epidemic or the culture behind it. The city has suffered 329 homicides in 2014, the Chicago Tribune reported, following 440 in 2013.

Lil Bibby, a 19-year-old at the forefront of the hardcore rap movement in a city nicknamed “Chiraq,” spoke in January on New York’s HOT 97 hip-hop radio station about gun violence in his hometown.

“In the last couple of years everybody got guns now, man. There ain’t no more fist fighting or arguing anymore, just guns,” Lil Bibby said. “Guns come out right away. There are kids, 13 or 14, playing with guns, and there ain’t no big homies telling them, ‘Stop this.’”

Several months later, HOT 97 debuted “Hot N—-” by the then-19-year-old from East Flatbush, Brooklyn, named Bobby Shmurda. The song is now ubiquitous on New York street corners, and it was blaring on repeat from a stereo across the street from the SOS South Bronx office on the day the whiteboard showed No. 95.

“Hot Boy,” as it’s called on the radio, reflects a pervasive gun culture that SOS staffers are fighting desperately to reform. Seven of the song’s first 10 lines, and most thereafter, draw on boastful anecdotes dealing with guns.

Although experts such as Redding note the peril of discounting underlying political causes behind crime, Save Our Streets is premised on changing a cultural mentality — as Butts put it, “accepting violence as normal behavior.”

“It’s not an easy thing or a quick thing, but I think it’s the only way you fix this problem,” he said. “If we continue to see community-level violence through the lens of a war on crime, it will just be a war on crime forever. It takes someone bold enough to say maybe there’s a new way to think about this problem.”

To keep urban shooting tallies like the one on the Mott Haven whiteboard low, must interrupters patrol violent street corners indefinitely?

“The foundational idea behind this model is that you implement it for three years or 10 years — some period of time — and you slowly shift away the social norms in support of violence, then you’re done,” Butts said. “There’s no need for people to be constantly funding programs to stop cigarette smoking: that cultural shift has already happened in this country. It’s the same thing with violence.”