Bronx River Alliance: Water pollution has been the highest in years

by Joasia E. Popowicz

Soundview Park boat launch. Photo credit: Joasia E. Popowicz

Take a right down O’Brien Avenue, where the traffic quiets down. The neat block houses transform into unruly fields, engines into birdsong. The asphalt walkway beginning at the intersection with Leland Avenue is patterned by golden afternoon sun and shadows cast by trees. A heavy sweet scent rests on the switchgrass. Fences marshal in the marshland to the left. Manhattan’s hazy chrome skyline fades into the horizon. Hip-hop blasts out of a fisherman’s boombox, across the reflective water.

This is Soundview Park: “Gateway to the River.”

Soundview Park. Photo credit: Joasia E. Popowicz

Bought by New York in the 1930s, the terrain was once marshland and open water. For the next 40 years, the area was used as a landfill, until civil engineering corps transformed the wasteland into a park. In 1992, the city’s first waterfront plan designated Soundview as a public open space for New Yorkers to enjoy access to the river.

Hugged by the Bronx River, the only freshwater river in New York City, the southernmost tip of the Soundview Park opens out into the East River where there’s a boat launch site.

But, water pollution levels have been consistently unsafe since testing began by the Bronx River Alliance in 2014.

Fishing in Soundview Park. Photo credit: Joasia E. Popowicz

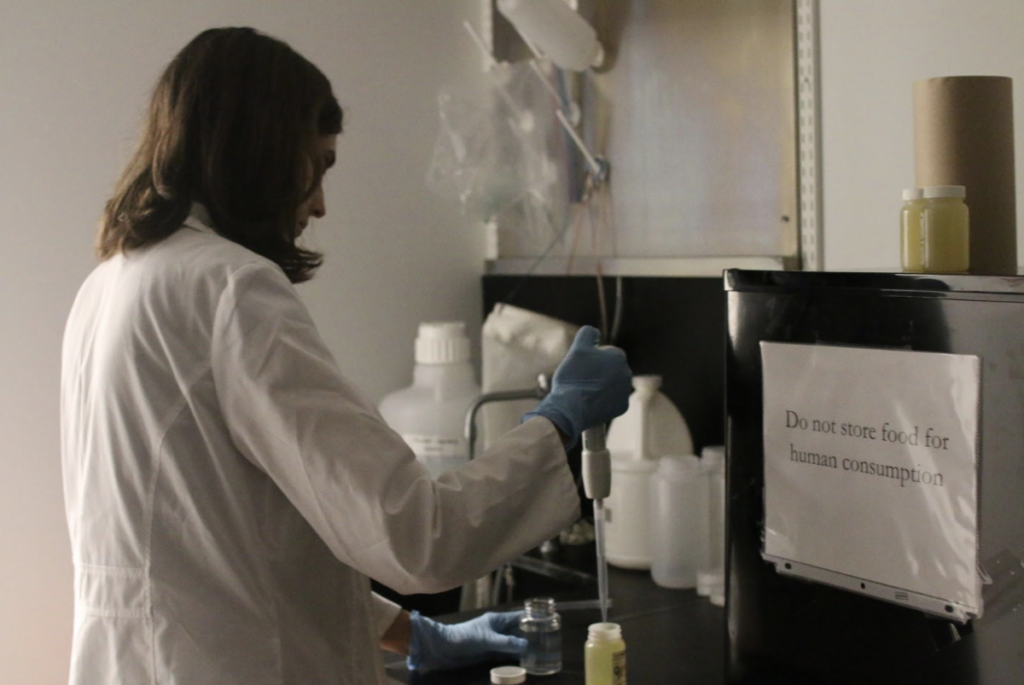

Downtown on a Thursday morning in Manhattan, Prof. Kate Good of John Jay Criminal College, put on her blue plastic gloves, against the outline of the George Washington Bridge. She’s testing a water sample for contamination. John Jay, is one of the partners in the Water Quality Monitoring Program, that processes the samples collected between Soundview and Starlight Dock. Every week, during recreation seasons, a group of scientists and volunteers collect samples from boat launch sites around the city. It’s the last day of the Community Scientist program, “but we’ll keep going throughout the year,” she said.

“The city also tests the water,” said Good. “But they don’t do it systematically.”

The initiative was started to combine efforts to address New York’s water pollution and flooding problem, though advocacy for the Bronx River dates back to the 1970s.

Prof. Kate Good taking water samples. Photo credit: Joasia E. Popowicz

Walking back up into the cavernous entrance to John Jay, Good lead the way to her lab, where she analyzed the water’s oxygen, saline and bacteria levels, to measure the health of water. She collects the samples on Thursdays, ready for analysis on Friday, so water users can know whether it’s safe for primetime use on the weekends.

They are searching for the presence of Enteroccocus bacteria, which indicates that raw sewage is entering the water. A safe level is 60 cells per 1,000 milliliters. This marker was established by the Environmental Protection Act and is based on an illness rate of 32 per 1,000 swimmers, or 3.2 percent.

At the one of the Soundview collecting sites on the Bronx River, the latest count was 503 cells per 1000 milliliters, over 8 times the safety threshold. Levels in the Bronx River have often been in the hundreds, and sometimes thousands, reaching 9,000 at the beginning of August this year.

By Soundview Park, where the Bronx River empties into the East River, the count reached over 24,000 cells per 1000 milliliters this August.

Prof. Good in her lab at John Jay College. Photo credit: Joasia E. Popowicz

“Levels have been the highest this year since records began,” confirmed Michelle Luebke, Director of Environmental Stewardship at the Bronx River Alliance, in a phone interview. “An ever an increasing population and climate change mean that when it rains, the system is overwhelmed.”

A conduit for industrial and residential waste for over 200 years, the Bronx River has slowly grown cleaner, but there’s a lot more to be done, Luebke said. Untreated sewage, mixed with rainwater contaminated with pollutants enter the river at Combined Sewage Overflows, or CSOs as they are commonly known. However, there are also many points at which sewage directly enters the water. Over 455 million gallons of untreated sewage enters the Bronx River each year, said Luebke. To address the problem, “there are a number of initiatives on community, non-profit and state and city-wide scale, however, coordination is difficult.”

Municipalities are required to map their separate sewage systems under state Environmental Conservation Law. However, they often fail to do this, said Luebke. The Bronx River Alliance is currently investigating illegal sewer flows.

One of the difficulties in the Bronx is that Westchester County owns the sewer mainline, whereas the municipalities own the lines going in. There is no agency structure that brings the municipalities and county together, and so that’s when Bronx River Alliance steps in.

Private entities are also contributing to the problem. Runoff from hard surfaces like big box stores and parking lots causes surges in water and waste. However, Luebke said, as long as these private entities pay the same water rate as small households, they have no incentive to tackle the problem. While the water rate remains the same, poorer communities, such as the Bronx, will continue to shoulder the burden.

Furthermore, even when there is state action, it is ineffective. Plans by the New York Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to invest $150 million claim that 170 million gallons of contaminated water will be prevented from entering the Bronx River. However, not only does this still leave 285 million gallons still entering the waterway, the plans proposed to simply redirect contaminated water into the East River, Luebke says. Other proposals for green infrastructure to be installed to absorb stormwater also fall short of addressing the scale of the problem.

The situation in the Bronx reflects a wider problem. City-wide, an estimated 21 billion gallons of untreated sewage water enters the city’s waterways every year, said Adam Forman, senior researcher at Urban Future, think tank. A study by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation estimated $36.2 billion of funding is needed to solve what has been described as a crisis.

At the moment, the battle is still being drawn out. The plans of the DEP triggered a lawsuit against the US Environmental Protection Agency to update its outdated water quality laws.

And the grassroots efforts continue. One of the community volunteers comes by Kate Good’s lab to drop off his samples. Why spend time volunteering? “I’m not spending my time,” he said. “I’m investing it.”

Back in Soundview Park, the sun sunk below the horizon. And the fishermen, tossed the fish they caught back into the water.

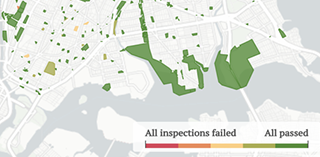

Tracking inspection records in Bronx public parks | Lucas Manfield

Tracking inspection records in Bronx public parks | Lucas Manfield Mapping amenities in Bronx public parks | Leafy Yan

Mapping amenities in Bronx public parks | Leafy Yan Acceptable or unacceptable: trash and inequality in two Bronx parks | Max Horberry

Acceptable or unacceptable: trash and inequality in two Bronx parks | Max Horberry The little west Bronx park that could, defying decade of cleanup efforts | Lucas Manfield

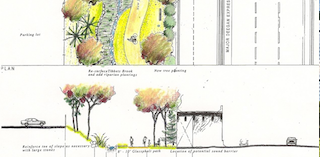

The little west Bronx park that could, defying decade of cleanup efforts | Lucas Manfield New life being brought to Tremont Park | Allen Devlin

New life being brought to Tremont Park | Allen Devlin Take out the old bring in the new: Soundview Park | Olivia Eubanks

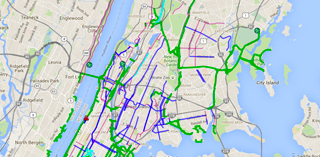

Take out the old bring in the new: Soundview Park | Olivia Eubanks Learning to bike in the Bronx | Virginia Norder

Learning to bike in the Bronx | Virginia Norder Private donors saved New York City parks—but for whom? | Brett Bachman

Private donors saved New York City parks—but for whom? | Brett Bachman Privatized puppy parks: a Bronx tail | Tristan Cimini

Privatized puppy parks: a Bronx tail | Tristan Cimini A Tale of Two Gardens | Tiya Thomas

A Tale of Two Gardens | Tiya Thomas Access to North and South Brother Islands still in question | Savannah Jacobson

Access to North and South Brother Islands still in question | Savannah Jacobson Is the Bronx not entitled to its own High Line park? | Beatriz Muylaert

Is the Bronx not entitled to its own High Line park? | Beatriz Muylaert Ongoing struggle to get recognition for slave burial ground at Joseph Rodman Drake Park | Aliya Chaudhry

Ongoing struggle to get recognition for slave burial ground at Joseph Rodman Drake Park | Aliya Chaudhry Bronx River Alliance: Water pollution has been the highest in years | Joasia E. Popowicz

Bronx River Alliance: Water pollution has been the highest in years | Joasia E. Popowicz Immigrants face barriers to Bronx parks | Seyma Bayram

Immigrants face barriers to Bronx parks | Seyma Bayram