Private donors saved New York City parks—but for whom?

by Brett Bachman

On a crisp October day, couples linger along meandering paths that crisscross Central Park, a canopy of leaves slowly changing color overhead. More than 40 million people visit here every year, whiling away leisurely afternoons at the Loeb Boathouse or on picnic blankets dotting Strawberry Fields, the Manhattan skyline looming just overhead. The park is an icon that’s come to embody New York City—and it’s treated as such, a landmark space with parts that are constantly being repaired, replaced and modernized.

Just eight miles north sits Van Cortlandt Park, another large island of green at the Bronx’s northwestern edge. Just below the park’s namesake train stop sit a series of large, 1930s-era stone bleachers, giving the adjoining stadium a distinctly Roman feel. Around the corner a renowned cross-country trail cuts through the landscape in zigs and zags, attracting runners from around the world who wish to test their mettle against the Bronx’s ridges and valleys. For as beautiful as the park can be, however, dilapidated amenities have taken their toll in recent years, causing bathrooms to close during big races and forcing hikers to abandon broken down bridges for fear of falling into polluted waterways plagued by leaky pipes and drainage problems.

A lack of funding often means problems languish in Van Cortland Park, like this eroded pathway along Van Cortlandt Lake. Photo credit: Brett Bachman

Though Van Cortlandt Park serves its own constituency of close to three million people annually, financial disclosure forms and public documents reveal that it garnered just under $800,000 in private donations and public maintenance funding last year. That’s compared to Central Park’s roughly $63.5 million tab, a sum that’s comprised mainly of donations from a well-heeled community living nearby. This population makes about two to three times the average citywide income, and stands to benefit, both through access and the resulting rise in property values that a well-maintained park provides.

In an era of government skepticism and tax cuts, experts say this disparity among New York City’s parks represents a small portion of a larger trend that’s seen the United States both abandon its commitment to providing public spaces and failing to provide an equal playing field for those who live outside wealthy enclaves like Manhattan.

“I think it’s telling of how we spend money in America, and it’s a telling sign of the retreat of public dollars from public life,” said John Surico, a research fellow at New York-based think tank Center for an Urban Future. He spent the bulk of the past year working on a comprehensive report on the city’s parks, and concluded that the system will need an influx of $6 billion during the next 10 years if the city wants to address a number of issues caused by decades of underfunding, largely in poorer districts.

“The city government can be so centrally located sometimes,” he said. “They concentrate so much on specific parks and it’s wild how little people know about others just because they’re outside the realm of wealth.”

The well-maintained Central Park of popular imagination, however, with its pristine grasslands and popular public gathering spaces, might seem almost alien to someone living in New York 40 years ago.

“In the 1970s if you wanted to find heroin, Central Park was probably the best place in the city to find it, other than Times Square,” said Steve Cohen, a parks advocate and the former executive director of Columbia University’s Earth Institute. “The great lawn was a dust bowl. It was a pretty rough place, the park was in complete disrepair.”

Today Central Park is generally considered clean, safe and well-traveled, though the city has largely stepped back from funding and running the space. Despite the fact that the park is still technically the city’s responsibility, it’s been managed for more than 35 years by the Central Park Conservancy, a privately run nonprofit that stepped in to clean up the park following a fiscal crisis in the 1970s that depleted the city’s coffers. Since then, the amount of public funding set aside for New York City parks has declined from around 1.3 percent of the total city budget to just over 0.6 percent today—a number Surico found to be well under what would allow for proper maintenance of public spaces.

The Conservancy’s fundraising success during a period of austerity—from $19 million in 2002 to more than $63 million last year, according to the organization’s tax forms—has subsequently ushered in a new age of public-private partnerships within New York City parks. More than 50 nonprofit organizations now exist to funnel hundreds of millions of dollars in private donations and grant money to city parks, revitalizing land that had for decades been at best a series of eyesores and at its worst some of the most dangerous real estate in New York City. The Parks Department did not respond to repeated requests for comment on this story, but city officials and many everyday residents maintain the arrangements free up money for other parks and ultimately are successful partnerships that can be replicated elsewhere.

But despite the positive effects on specific parks under this model, the past 40 years have also marched a long trend toward inequity as wealthier areas of the city invest in their neighborhood’s parks with both money and volunteer hours, while outer boroughs and poorer sections of the city are forced to make do with the shrinking slice of funding and staffing the city is willing to provide.

“The city finds a way to fund its signature parks, but there just isn’t enough money to go around and other parks are just not a priority,” said Christina Taylor, executive director for the Friends of Van Cortlandt Park. “The people who use them deserve more than what they’re getting.”

A volunteer works to maintain one of Van Cortlandt Park’s many baseball fields. Photo credit: Brett Bachman

Though a quarter of the Bronx is zoned as parks land—with more acreage than any other borough—it received less taxpayer-financed maintenance funding last year than Manhattan, Brooklyn or Queens, according to the Center for an Urban Future. Though maintenance makes up about one-fifth of the Parks Department budget, it provides some insight into where taxpayer dollars are going. Officials said many of the department’s expenditures are difficult to track because staff, equipment and vehicles all travel between parks and often between boroughs. But Surico said it’s safe to say that without Manhattan’s central location or large number of tourists, it’s difficult for the Bronx or its parks to gain the attention of City Hall.

“Central Park is great, and I do think it’s one of the best parks in the world—but why wouldn’t anyone from other boroughs want to come to somewhere like Van Cortlandt Park?” Surico asked, pointing to amenities like the country’s first public golf course, a world-class cross country trail and the Bronx’s largest freshwater lake. Still, as he walked through the spine of Van Cortlandt Park on a cloudy October day several problems arose, such as a section of the park’s pathway that had washed away after a recent rainstorm. Sitting in its place was a large, impassable puddle and a line of people tiptoeing around in an attempt to keep their feet dry.

“People still love these parks and use them, even with this myriad of problems,” Surico said. “I think that really just highlights the urgency we’re trying to get across.”

A washed out path illustrates the dangers of poor drainage and maintenance in Van Cortlandt Park. Photo credit: Brett Bachman

The flooded path was also a location that Taylor pointed out on a recent walk through the area. Two nonprofit organizations serve to raise money and fix problems like this, the Friends of Van Cortlandt Park and the Van Cortlandt Park Conservancy. However, the park saw a combined $483,182 from both last year, according to public tax documents. At 300 acres and nearly a third smaller, Central Park received nearly $54 million from its conservancy. Meanwhile, both parks saw a fraction of that money from the city.

These disparities stem from the way New York City funds its public spaces, Surico said, with City Council members as the sole unit in charge of parks funding in their districts. Most of the money for parks comes out of a general pool of tax dollars, meaning other concerns—usually ones that have high name recognition and can drive votes—often take precedence.

“Council members in more disadvantaged neighborhoods have like, 10 other problems they’ve got to give money to,” he said. “Community health, clinics, libraries, they’ve got a lot of crime, and you can see how parks fall down the priority list.”

Other cities across the country have successfully explored alternative models to remove these electoral concerns from the equation. Minneapolis and Chicago, for example, have separate, elected boards that serve to manage the cities’ park land, as well as dedicated tax and revenue streams that only serve parks.

The sheer size of New York City also makes it difficult to hold referendums that elsewhere serve as a critical source of funding for parks. It’s much more difficult to convince someone in Staten Island that their tax dollars should fund a minor park in the Bronx than if the vote were simply held in Bronx County. Contrast this with a slightly smaller city like Dallas, where a successful referendum last year dedicated a $1 billion bond package to construction on four new downtown parks.

But it’s not all bad news, says Cohen, who has written about and studied New York City parks for decades. “There’s been more capital money going into parks in the last 20 years than in the preceding 20 years,” he said, noting that both former Mayor Michael Bloomberg and current Mayor Bill de Blasio have invested more in the city’s parks than their immediate predecessors. A booming economy also means there’s more money to go around.

“I think there’s starting to be a reawakening right now,” Surico said. “People are realizing how important parks are, people are starting to realize how important things like libraries and public transit are. You look at any city that’s coming up right now and they’re focusing on these things.”

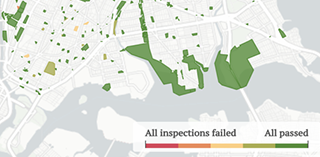

Tracking inspection records in Bronx public parks | Lucas Manfield

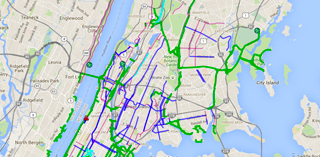

Tracking inspection records in Bronx public parks | Lucas Manfield Mapping amenities in Bronx public parks | Leafy Yan

Mapping amenities in Bronx public parks | Leafy Yan Acceptable or unacceptable: trash and inequality in two Bronx parks | Max Horberry

Acceptable or unacceptable: trash and inequality in two Bronx parks | Max Horberry The little west Bronx park that could, defying decade of cleanup efforts | Lucas Manfield

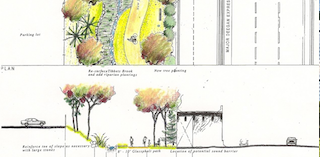

The little west Bronx park that could, defying decade of cleanup efforts | Lucas Manfield New life being brought to Tremont Park | Allen Devlin

New life being brought to Tremont Park | Allen Devlin Take out the old bring in the new: Soundview Park | Olivia Eubanks

Take out the old bring in the new: Soundview Park | Olivia Eubanks Learning to bike in the Bronx | Virginia Norder

Learning to bike in the Bronx | Virginia Norder Private donors saved New York City parks—but for whom? | Brett Bachman

Private donors saved New York City parks—but for whom? | Brett Bachman Privatized puppy parks: a Bronx tail | Tristan Cimini

Privatized puppy parks: a Bronx tail | Tristan Cimini A Tale of Two Gardens | Tiya Thomas

A Tale of Two Gardens | Tiya Thomas Access to North and South Brother Islands still in question | Savannah Jacobson

Access to North and South Brother Islands still in question | Savannah Jacobson Is the Bronx not entitled to its own High Line park? | Beatriz Muylaert

Is the Bronx not entitled to its own High Line park? | Beatriz Muylaert Ongoing struggle to get recognition for slave burial ground at Joseph Rodman Drake Park | Aliya Chaudhry

Ongoing struggle to get recognition for slave burial ground at Joseph Rodman Drake Park | Aliya Chaudhry Bronx River Alliance: Water pollution has been the highest in years | Joasia E. Popowicz

Bronx River Alliance: Water pollution has been the highest in years | Joasia E. Popowicz Immigrants face barriers to Bronx parks | Seyma Bayram

Immigrants face barriers to Bronx parks | Seyma Bayram