Access to North and South Brother Islands still in question

by Savannah Jacobson

North and South Brother Islands from Barretto Point Park. The North is on the right closer to the foreground, the South, slimmer than its kin, is on the left. Photo credit: Savannah Jacobson

The East River is peppered with small islands filled with larger-than-life New York City history.

Two of them sit at the northern mouth of Hell Gate, a stone’s throw away from Barretto Point Park in Hunts Point. They provide some of New York City’s most enigmatic storytelling: in the north lies the old hospital that once housed Typhoid Mary, and the southern island harbored rum runners during Prohibition.

Today, if any Bronx adventurer wants to visit North or South Brother Island, they’ll probably have to find a Parks Department-approved scientist with spare room in their kayak. An eagerness to find the elusive northern dusky salamander, or being deemed the Greenest New Yorker by the state government might also help. Erik Baard, a regular explorer of South Brother Island and founder of environmental group HarborLAB, falls into both camps.

To adventurers like Baard, the island’s allure remains about the scrappiness required to get there. In the mid-2000s, he bonded with a Parks Department official over their search for the rare swamp-loving salamander. Now, all he needs to get to South Brother Island is some advanced notice.

“In the early days it was a little bit more radical seeming,” said Baard. “But now I’m 50 and I have white hair, and they know I’ve been doing it, so it’s fine.”

The twin isles reside between Rikers Island and the Bronx mainland, their upkeep reliant on a mired-down government that wrestled the land out of the hands of New York elite.

While North Brother Island has been uninhabited since 1963, only a scarce few have seen South Brother Island’s light of day since 1909.

The city has intended to make North Brother Island publicly accessible for decades, but the effort has stalled—the Parks Department only allows for visitation from academics and scientists. And South Brother Island remains strange and vacant, a land strictly reserved for some of the East Coast’s most exotic fauna, or the occasional message in a bottle.

On one of his earliest ventures, Baard discovered a bottle with a note inside dating back to the ‘80s.

“He had thrown it from Hunts Point,” said Baard. “It washed up on the island and stayed there. That’s how stable things were before Hurricane Sandy, it hadn’t left the East River for 30 years.”

Indeed, stability defines the history of South Brother Island.

In the early 20th century, Col. Jacob Ruppert, a brewer and owner of the New York Yankees, owned the island. Stories of booze smuggling in the ‘30s run rampant, but the island’s reigning tale surrounds the intrigue that stems from its emptiness.

Meanwhile, North Brother Island’s history is colored with tumult and tragedy, until it reached its final fate: entanglement in the nests of bureaucracy.

Parks Department sign in Barretto Point Park commemorating the shipwreck. Photo credit: Savannah Jacobson

In 1904, a steamship carried German churchgoers from the Lower East Side to Long Island for a Sunday School jaunt. Somehow, a spark lit in a storage room that kept barrels of oil. The fire spread through the ship just as it reached Hell Gate. The ship captain hurtled forward to North Brother Island, but over a thousand passengers had already perished.

Several years later, Mary Mallon, an Irish immigrant working as a cook, tested positive for tuberculosis. The Department of Health forced her into quarantine on North Brother Island where, apart from a five-year reprieve, she would live the rest of her life in isolation. The lore of Typhoid Mary’s quarantine attracts the city’s lovers of all things creepy, medical, and abandoned.

An illustration of Mary Mallon featured in a 1909 edition of defunct newspaper “New York American.” Photo credit: Museum of the City of New York, on Instagram

Still etched into the walls of a decrepit hospital lie an inmate’s infamous words: “Help me I am being held here against my will.”

A haunting wall carving in an abandoned hospital on North Brother Island. Photo credit: Ian Ference/The Kingston Lounge

Following the close of World War II, the city rotated through purposes for North Brother Island, from veteran housing to youth rehabilitation centers, until finally shuttering everything in 1963, vacating the island indefinitely and leaving behind 26 empty structures.

Now, after sitting uninhabited for decades, traveling to North Brother Island requires good timing, a permit from the Parks Department, and an advanced degree or elected position.

“We are currently only accepting requests to visit with a rigorous academic focus and institutional association,” said Parks Department analyst Tely Renata. All visitors are prohibited during bird nesting season, from late March to late September.

This restrictiveness contrasts the political rhetoric surrounding North Brother Island.

“What’s wrong with making North and South Brother Islands accessible?” asked Bronxite Jonathan Marin in a Facebook group.

The answer? It depends on who you ask.

Councilman and former parks chair Mark Levine visited the island in 2014, setting off rumors about North Brother Island opening to the public.

“I hope you wouldn’t have to be a city councilman to see this,” he told Gothamist at the time.

Levine’s visit coincided with a periodic study from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design to create a responsible plan that would allow for public visitation. The study, released last year, exposed the tension at the heart of the fight over who gets to visit North and South Brother Islands: ecologists are concerned with environmental protection and preservation, while community groups see opening the island as a way to increase access to green space and potentially provide jobs in the South Bronx.

“I am very much opposed to making North and South Brother Island any sort of public park,” said Baard. “I think we’ve eaten up enough land in New York City as a species. I think it’s not asking too much to leave some of it aside for other species.”

At the same time, Baard is sympathetic to the lack of reachable green spaces in neighborhoods like East Harlem, where Randall’s Island is counted as open space: “That’s obscene in a lot of ways to say, ‘Don’t worry, you’ve got your green space, just walk all the way there.’”

The University of Pennsylvania study ultimately recommended a trial period of limited and controlled public access.

“It requires thinking in different terms about what open to the public means,” said Randall Mason, the study’s principal investigator and Associate Professor of historic preservation at the University of Pennsylvania. “It would certainly be seasonal and that’s in keeping with the ecological preservation imperative. It would mean to be deliberate and intentional about the usage of the park.”

Since the study was published, the city has not shown much progress in opening the island. Still, Mason has faith that the Parks Department and a coalition of private partners will find funding for a successful pilot period of public access.

“Parks funding will always be the bottleneck. As long as that could be solved, there are avenues that could be explored.”

Signage in Barretto Point Park from a coalition of groups that helped New York City purchase South Brother Island. The island can be seen on the left. Photo credit: Savannah Jacobson

As for South Brother Island, the Trust for Public Land, a conservation non-profit, negotiated the land from private ownership into full oversight by the Parks Department in November 2007. U.S. Rep. José Serrano, whose district includes the islands, worked with a coalition of environmental-minded nonprofits to secure $2 million in federal grant funds to facilitate the land transfer and preserve the island as a bird sanctuary.

For now, in a borough where locals’ needs are rarely met and on two islands that have lived in obscurity for centuries, it seems that even more so than lacking a PhD in marine biology, boating equipment, or wings, public opinion and bureaucracy are still the biggest impediments to ever reaching the islands.

Baard doesn’t see the problem. Some places, he says, should be left untouched.

“I don’t romanticize things as much.”

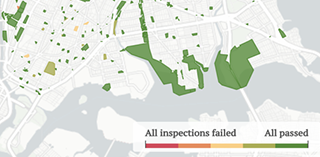

Tracking inspection records in Bronx public parks | Lucas Manfield

Tracking inspection records in Bronx public parks | Lucas Manfield Mapping amenities in Bronx public parks | Leafy Yan

Mapping amenities in Bronx public parks | Leafy Yan Acceptable or unacceptable: trash and inequality in two Bronx parks | Max Horberry

Acceptable or unacceptable: trash and inequality in two Bronx parks | Max Horberry The little west Bronx park that could, defying decade of cleanup efforts | Lucas Manfield

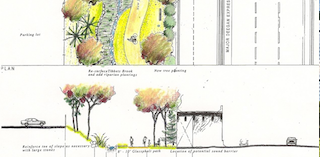

The little west Bronx park that could, defying decade of cleanup efforts | Lucas Manfield New life being brought to Tremont Park | Allen Devlin

New life being brought to Tremont Park | Allen Devlin Take out the old bring in the new: Soundview Park | Olivia Eubanks

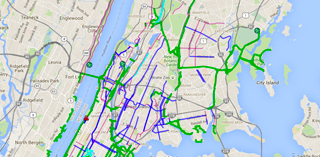

Take out the old bring in the new: Soundview Park | Olivia Eubanks Learning to bike in the Bronx | Virginia Norder

Learning to bike in the Bronx | Virginia Norder Private donors saved New York City parks—but for whom? | Brett Bachman

Private donors saved New York City parks—but for whom? | Brett Bachman Privatized puppy parks: a Bronx tail | Tristan Cimini

Privatized puppy parks: a Bronx tail | Tristan Cimini A Tale of Two Gardens | Tiya Thomas

A Tale of Two Gardens | Tiya Thomas Access to North and South Brother Islands still in question | Savannah Jacobson

Access to North and South Brother Islands still in question | Savannah Jacobson Is the Bronx not entitled to its own High Line park? | Beatriz Muylaert

Is the Bronx not entitled to its own High Line park? | Beatriz Muylaert Ongoing struggle to get recognition for slave burial ground at Joseph Rodman Drake Park | Aliya Chaudhry

Ongoing struggle to get recognition for slave burial ground at Joseph Rodman Drake Park | Aliya Chaudhry Bronx River Alliance: Water pollution has been the highest in years | Joasia E. Popowicz

Bronx River Alliance: Water pollution has been the highest in years | Joasia E. Popowicz Immigrants face barriers to Bronx parks | Seyma Bayram

Immigrants face barriers to Bronx parks | Seyma Bayram