Immigrants face barriers to Bronx parks

by Seyma Bayram

The sun was about to set at Williamsbridge Oval Park in the Bronx, but the action was just getting started.

A group of Mexican and West African young men changed into sneakers in the middle of the soccer field. Their brightly colored jerseys — featuring the greens and reds of the Mexican national team and the light blue of Argentina — contrasted with the gray sky at dusk. At the field’s western end, Yemeni boys practiced shooting into a goalpost without a net. Across from them, a third group from Ecuador played futsal, a variation of soccer played on a hard court with a smaller, firmer ball.

About 60 people crowded the field, situated in the middle of the communities of Norwood and Olinville. With fall officially in season and fewer daylight hours, the players anxiously waited for their last teammates to arrive. Around 6:30pm, the games began.

“Lights. We need lights,” said one soccer player, who is originally from Guinea but arrived in the Bronx from Maryland to complete his medical residency. He was referring to the lack of lamp posts to illuminate the field. “You see the time people are showing up to play. We literally have 20 minutes to play before it’s dark,” he added.

The hours of operation for most parks are based on traditional 9-to-5 working schedules, and as such, they do not always accommodate the leisure opportunities afforded to immigrants, who often work longer hours and irregular shifts. It was the reality on the Williamsbridge Oval that night, and one of the findings in a report titled “Parks for All New Yorkers: Immigrants, Culture, and NYC Parks,” published in 2008 — shortly after Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced city-wide legislation requiring all public agencies to create a language access plan to make their resources accessible to non-English speakers.

New Yorkers for Parks, an independent non-profit agency that seeks to improve park quality for the city’s residents, conducted the research to better understand park-related issues faced by immigrant groups.

Not much has changed since 2008, but it’s only recently that immigrants and advocacy groups have begun to raise awareness around whether or not urban parks are accessible to immigrants. Despite accounting for more than one-third of New York City’s population, immigrants continue to face significant linguistic, material, and bureaucratic barriers to parks access, according to New Yorkers for Parks. In the Bronx, where immigrants make up 37 percent of the total population, the issue is especially prevalent.

The report identified language barriers as the most obvious obstacle to inclusivity. Language barriers included lack of signage in other languages, but also translator services for park-related meetings.

But it also identified other, less obvious barriers.

The permit application process requires access to a computer and WiFi, and in many parks there is an informal grandfathering system that gives preference to existing permit holders regardless of applications from new groups. Moreover, the report found that park use — including recreational activities and sports preferences — varied greatly across different immigrant populations.

The soccer field at Williamsbridge Oval Park is mixed-use, meaning that it doubles as a football field. This can be a source of tension for immigrant soccer players and members of the local football teams. The Bronx Buccaneers and Bronx Knights youth tackle football teams have rights to the field four days of the week.

“The American football team has a permit, so we don’t usually have enough space to play,” said Brian Rodriguez, 21, a Mexican player who is also a third year psychology student at Hunter College.

Despite this, most park design, with its standard sports fields based on Americans’ preferences, did not reflect the diversity in immigrant users’ recreational habits or the increased demand for certain fields because of a specific demographic. At Williamsbridge Oval Park, there isn’t enough space on the single soccer field to accommodate everyone.

The struggle to acquire more space is exacerbated by the lack of translation services offered by public agencies. This is a citywide issue that has been a focus for Councilman Ritchie Torres of the Bronx, who wants to put an end to linguistic barriers preventing non-English-speaking members of communities from participating in civic life and decision-making processes in their neighborhoods. He co-sponsored a bill in January 2018 that would require city agencies to offer free translation services at every public meeting in a neighborhood where 10 percent or more of residents speak a language other than English.

Although 35 percent of residents in Norwood identify as having limited English-language proficiency, meetings hosted by the Parks Department and community council currently do not offer translation services.

The Friends of Williamsbridge Oval, a group of park users who serve as intermediaries between the community, the Parks Department, and elected officials in matters relating to park users’ needs, acknowledged that more needs to be done to enhance the park experience for Norwood’s immigrant populations.

“The issue of language is something I’ve been wanting to address,” said the group’s secretary, Betty Diane Arce, who is also a member of the local community board. She noted that translator services are not offered at meetings hosted by public agencies.

“It’s access to education too. There are programs to learn the English language for Spanish-speakers, but not for the rest of them,” added Sheila Sanchez, president of Friends of Williamsbridge Oval. She is referring to the lack of English language education options designed with speakers of other languages, such as Bengali — a language spoken by many Norwood residents — in mind.

In addition to linguistic and bureaucratic barriers, fears around immigration status, especially in a political environment that is increasingly hostile to the nation’s foreign-born population, may further alienate immigrants. While residents can join in on public meetings and apply for permits, some may opt not to out of fear.

“Immigration status keeps a lot of people from being a little more proactive and making demands,” said Arce.

In order to request a new sports field, a group would have to create a petition and gather 100 to 500 signatures. That petition must be brought before the Community Board, from which the group would request a letter of recommendation that is then presented to elected officials.

Until then, soccer and futsal players at Williamsbridge Oval Park will continue to play into the dark.

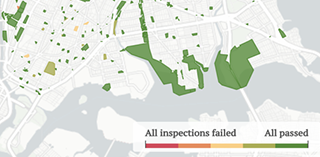

Tracking inspection records in Bronx public parks | Lucas Manfield

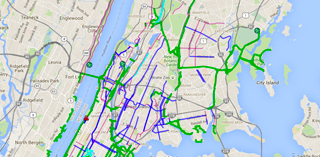

Tracking inspection records in Bronx public parks | Lucas Manfield Mapping amenities in Bronx public parks | Leafy Yan

Mapping amenities in Bronx public parks | Leafy Yan Acceptable or unacceptable: trash and inequality in two Bronx parks | Max Horberry

Acceptable or unacceptable: trash and inequality in two Bronx parks | Max Horberry The little west Bronx park that could, defying decade of cleanup efforts | Lucas Manfield

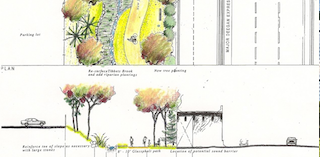

The little west Bronx park that could, defying decade of cleanup efforts | Lucas Manfield New life being brought to Tremont Park | Allen Devlin

New life being brought to Tremont Park | Allen Devlin Take out the old bring in the new: Soundview Park | Olivia Eubanks

Take out the old bring in the new: Soundview Park | Olivia Eubanks Learning to bike in the Bronx | Virginia Norder

Learning to bike in the Bronx | Virginia Norder Private donors saved New York City parks—but for whom? | Brett Bachman

Private donors saved New York City parks—but for whom? | Brett Bachman Privatized puppy parks: a Bronx tail | Tristan Cimini

Privatized puppy parks: a Bronx tail | Tristan Cimini A Tale of Two Gardens | Tiya Thomas

A Tale of Two Gardens | Tiya Thomas Access to North and South Brother Islands still in question | Savannah Jacobson

Access to North and South Brother Islands still in question | Savannah Jacobson Is the Bronx not entitled to its own High Line park? | Beatriz Muylaert

Is the Bronx not entitled to its own High Line park? | Beatriz Muylaert Ongoing struggle to get recognition for slave burial ground at Joseph Rodman Drake Park | Aliya Chaudhry

Ongoing struggle to get recognition for slave burial ground at Joseph Rodman Drake Park | Aliya Chaudhry Bronx River Alliance: Water pollution has been the highest in years | Joasia E. Popowicz

Bronx River Alliance: Water pollution has been the highest in years | Joasia E. Popowicz Immigrants face barriers to Bronx parks | Seyma Bayram

Immigrants face barriers to Bronx parks | Seyma Bayram