Posted on 23 October 2012.

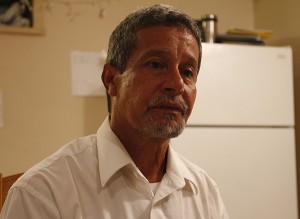

The rapping professor of African American Studies and History wonders whether too much testing is affecting Bronx public school children’s health. (VALENTINE PASQUESOONE/The Bronx Ink)

The seeds for activist Professor Mark Naison’s latest cause were laid nine years ago. That’s when he began directing the Bronx African American History Project run by Fordham University, a project documenting the experiences of blacks in the Bronx.

Four years ago, the teachers in the 13 public schools involved in the project began telling Naison they had no time to devote to it anymore.

The reason? Standardized tests. Naison began to understand that test scores had become more and more high stakes under Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration, determining whether schools closed down and teachers and students were promoted.

“It wasn’t one day, it was an accumulation of things,” said Naison, whose broad chest and vigorous delivery make him look younger than his 66 years. “But it was also pretty clear that I wasn’t going to be invited into particular schools.”

Naison had been involved in community service and radical causes for most of his life. From the Civil Rights movement of the 1960’s to coaching sports programs to his current fight against stultifying tests, he brings a provocative intensity to everything he does.

“His fierce commitment and determination and tenacity, everything that made him a ferocious athlete, he brings that into his relationships as an activist and as a friend,” said Mark Chapman, an associate professor of African and African American Studies at Fordham and pastor at Hollis Presbyterian Church in Queens. Chapman is a close friend of Naison’s and a fellow protester.

Naison’s passion for protest displayed on his office door. (VALENTINE PASQUESOONE/The Bronx Ink)

Recently, Naison landed on another wrinkle in the standardized test problem, one that promised to make a stir. Last year, his Fordham students conducting research in public schools told him that students were not getting any exercise and that preparation for the tests were a likely cause. The tests, he reasoned, took precedence over recreation. After-school programs had been turned over to studying rather than playing.

Naison, a successful athlete in high school and college, took it personally. For the hyperactive, rebellious child, physical activity was necessary for Naison to release pent-up energy. He worried that today’s Bronx children did not have the same opportunity.

“If you don’t give kids who are like me a physical outlet during the day, they’re going to flip,” Naison said.

Naison cited a report called Food, Fitness, Obesity and Diabetes in the Bronx by Jane Bedell, Assistant Commissioner at the Bronx District Public Health Office, which indicated that less than half of South Bronx public high school students reported attending physical education class three times a week. Sixty-four percent of the borough’s teens meet this state standard, compared to 74 percent of the city’s kids.

Tests may be one reason, Naison said. Gentrification and housing policies, another. In a post on his blog “With A Brooklyn Accent” he said people who move to the South Bronx to escape gentrified areas spend most of their income on rent and have little time for fitness or physical activity. Naison also argues housing policy contributes to health problems because recreation centers are not created in proportion with new housing facilities, resulting in a lack of physical activity space.

It’s a theory, unproven in parts, but all aspects point to a formula for a good protest – anti-authority, injustice and marginalized underdogs.

Naison developed his love for protest and sports growing up in the Crown Heights and Flatbush sections of Brooklyn in the 40’s and 50’s. Whether it was in school or at a local park, Naison played one sport or the other, from basketball to tennis to dodge ball – or “bombardment” – as he used to call it. He was also a standout student, skipping both the third and eighth grades.

Tennis and basketball became his two best sports, and he ended up playing tennis as an undergraduate at Columbia University, receiving an academic scholarship that took care of almost half his tuition. He became captain of the school’s tennis team and stayed involved in athletics after graduating in 1966, coaching in sports programs in Park Slope, where he now lives.

Naison’s parents threatened to send the young rebel to military school. He enjoyed the roll of intimidator, cultivated first on the playing field in the neighborhood, and later on the streets and classrooms as an activist. He is as loyal to his friends as he is hostile to his enemies.

His success both in the classroom and on the athletic fields got to Naison’s head, giving him a cocky attitude, and it was activism that tempered his worldview by showing him the plight of the marginalized. He took part in the Civil Rights movement and advocated for tenants in East Harlem during his undergraduate years at Columbia. He got his Master’s and PhD at Columbia and took part in school protests against the Vietnam War and the Morningside Gym in 1968. Naison, who was among the activists who protested at Hamilton Hall on the Columbia campus, said students were against the school’s research for the Defense Department and the gym, which would have been built on public ground at Morningside Park.

The nation’s attitudes about race became personal for Naison in 1965, when he began a six-year relationship with a black woman he calls Ruthie. His parents, though sympathetic to the Civil Rights cause, did not approve of their son’s relationship. The reaction from those who saw the two together further drove Naison towards studying race.

“We were like a Rorschach test for the societies,” Naison said. “Just the two of us walking arm-in-arm, hand-in-hand down the streets, it was like people didn’t know what to do with us.”

While a PhD student he was offered a job at Fordham’s then-new African and African American Studies department in 1970. Not everyone was willing to accept a white man into an African American studies program, but, true to form, Naison did not back down.

His athletic prowess gave him credibility. Naison said he played basketball with the Fordham team and became friendly with black players. He also was not afraid to glare at those who shot him dirty looks, sending a non-verbal message that he would not back down. Naison is proud of this stare – or “ice grill” – which is easy to imagine when looking at his deep eyes, which lock on their targets like a vulture’s on its prey.

Naison’s menacing stare is now directed at the U.S. Department of Education’s Race to the Top policy that provides funding for states that agree to implement reforms that include teacher evaluations that place a strong emphasis on standardized test scores. These scores account for up to 40 percent of the criteria for New York’s teacher evaluations. Low-performing schools can close and teachers whose students do not score well on these tests can lose their jobs. Naison said this creates an environment of fear in schools, as teachers and principals constantly wonder if they will be fired.

New York was chosen by the federal government to receive $700 million in Race to the Top funds in August 2010 and has been struggling to comply with its criteria ever since. In January 2012, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan gave the state a stern warning to finalize the teacher evaluation system, which the state and its teachers union could not agree upon. The two parties agreed to a plan in February, just before the deadline set by Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

Race to the Top not only gives Naison something to protest, it brings out his bravado. He is not shy about calling out President Obama, Cuomo and other powerful figures who he said cannot adequately set education principles.

“I have this persona, I know I’m unreasonable sometimes, but what you see is what you get,” Naison said. “I’m going to tell you what I think, I’m going to say it as clearly as I can, and if I’m wrong I’ll admit I’m wrong, but if I’m right I’m going to stand up for what I believe in and you’re not going to be able to knock me off course.”

“You’re not going to be able to knock me off course,” Naison said. (VALENTINE PASQUESOONE/The Bronx Ink)

Naison is admittedly arrogant and has no doubts about the credibility of his opinions, though he did admit to not being an expert on state education policy. He gets his information from the students and teachers he keeps in touch with, and from his wife Liz Phillips, principal of P.S. 321, a high-achieving school in Park Slope.

Though Naison – the self-appointed “teacher’s defender” – may not have expertise in the field, he is equipped with a position of authority.

“Teachers can’t speak out for themselves very easily,” Naison said. “I’m a tenured full professor at a university in the latter stages of my career, there’s no retaliation.”

Tenure combined with intimidation tactics has led to resistance-free activism. Naison is confident he has critics, but has not heard from any, which he attributes to his brash style that may ward off direct confrontation.

Naison’s beliefs are undoubtedly unorthodox, making them susceptible to scrutiny. Eric Nadelstern, a professor of practice at Columbia Teacher’s College and former deputy chancellor of the New York City Department of Education, cited poverty and corruption in the Bronx as more significant contributors to the borough’s health problems.

“There was a health crisis for Bronx kids in public schools decades before standardized testing became a value in evaluating schools and teachers,” said Nadelstern, founder and former principal of the International School at LaGuardia Community College in Queens. “So to say this is what’s responsible for the health crisis for Bronx kids is easy to say but very difficult to prove.”

Nadelstern supports the use of standardized tests as a means of comparing schools, and said making them account for 40 percent would allow them to contribute to the teacher evaluation but not dominate it. He shared Naison’s dislike of Race to the Top, saying it was not doing a good job of evaluating teachers, but he did say the program was prioritizing evaluation and accountability, something he said was crucial to improving standards.

Naison was critical of value-added measures, which take into account a student’s year-to-year performance in standardized testing to better understand a teacher’s effectiveness. Jonah Rockoff, an associate professor of finance and economics at Columbia University Business School, who has written about teacher evaluations and value-added measures, believes the current teacher evaluation system is more effective than earlier ones that were too lenient.

“I want to hear the alternatives,” Rockoff said. “Because the alternative to say let’s go back to the old system where 99 percent of people get an ok, that just doesn’t seem better.”

Naison said a more holistic approach to student learning and peer-based evaluations could help, but does not anticipate changes anytime soon. He voices his concerns on his blog and has accumulated a large online following of teachers.

He also uses hip-hop to express himself, in the form of raps performed by his alter ego “The Notorious PhD.” He is a student of hip-hop, as he demonstrated in his appearance on “Chappelle’s Show,” Dave Chappelle’s hit program on Comedy Central, in a game show skit called “I Know Black People.”

Naison’s passions and forms of expression may not be what one expects from a white man of retirement age, but conventional wisdom does not do much good when taking on the policies of a mayor, governor and president. Instead, what is required is a zeal for defying authority and an in-your-face arrogance that must be displayed even when the mission’s success is in doubt.

“I’m not optimistic, it’s just that I’m right,” Naison said of his anti-standardized test activism, “because I’ve been a teacher and a coach all my life.”