As war progressed in Kosovo in 1999, 7-year-old Ariana Metalia sat in front of the television in her family home in New York and watched the bloodshed taking place more than 4,000 miles away.

“My parents didn’t hide anything from us. Every day we came home from school, we would watch the news,” said Metalia. “They wanted us to see what was going on.”

Metalia, a first-generation Albanian-American whose parents immigrated to the Bronx from mainland Albania, is one of an estimated 100,000 Albanians currently living in New York City.

The majority of Albanians to emigrate between the 1970s and 1990s, did so as refugees. Like Metalia’s immediate family, some came fleeing political persecution under communist rule in Albania; others fled war in Former Yugoslavia, where ethnic Albanians in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Kosovo were the targets of ethnic genocide.

Despite having never lived through the violence first-hand, Metalia represents a community of Albanian-Americans born in New York City after their parents immigrated. It’s a generation left to grapple with the impact of familial trauma.

Now, she is part of a team of young Albanians working to establish a mental health day for the Albanian community. The event would be the first of its kind to address what she said is a need for open conversation about trauma and grief.

“Because my parents were so active in supplying weapons and funding to help my cousins rebuild their homes during the war, I felt like we were a part of it,” said Metalia. “Nobody in my family died in Kosovo, but it’s just been drilled into my head how devastating these situations were.”

Metalia, whose childhood experiences led her to pursue a career as a licensed mental health counselor, said that the exposure to trauma, combined with a cultural stigma against getting help in Albanian communities has taken its toll.

“People are walking around like zombies with post-traumatic stress disorder, and nobody is doing anything about it,” said Metalia. “People can get better if you provide the resources for them, but I mention therapy and Albanians look at me like I’m delusional.”

That’s something that she is hoping to change.

Inherited trauma and unspoken grief

Vlash Parubi doesn’t like his wife’s Okra stew.

The traditional dish—called Bajme in his native Albanian language—is a savory blend of onion, garlic, tomato and lamb, simmered with the summertime vegetable until the flavors fuse.

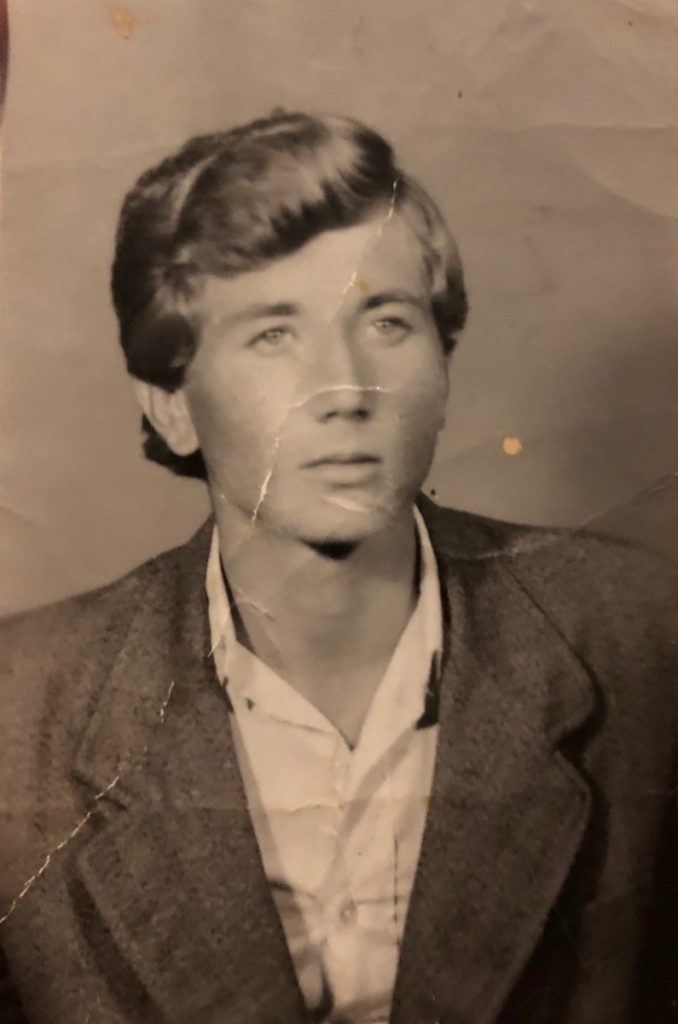

To his family in the Bronx, the stew is a piece of cultural heritage, but to Vlash, Bajme is a sore reminder of an earlier life lived out under communist reign. Like most young men who grew up in The Eastern Bloc, Vlash served mandated time in the Albanian national military before immigrating to New York as a political refugee in 1990.

He doesn’t speak much about what happened during his two years of service in the mid 1980s— a decade in Albania defined by economic hardship, violent imprisonment and global isolation—but one of the few things his children have come to understand about that time in their father’s life, are his eating habits. For dinner in the military, he’d eat Bajme every single day.

Now, he can’t bear the thought of the taste.

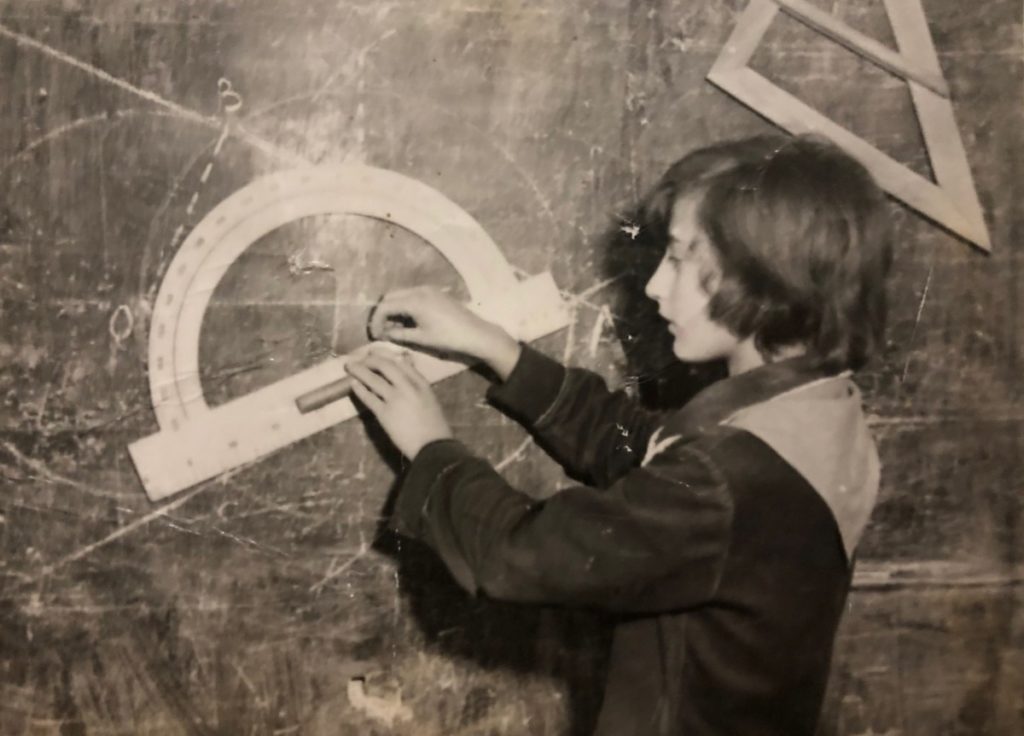

Maria Parubi is Vlash Parubi’s oldest child.

The 23-year-old’s Instagram account is decorated with photos of beautiful Albanian landscapes and portraits of her posing in front of them.

In one photo, she stands alone, wearing a white dress, speckled in blue, while looking out onto a jagged mountain range covered in patches of dark greens that turn pastel under the shadows cast by the clouds above. In another, she stands smiling with her brother as the sun sets on a village in the backdrop. Her caption reads, “Home is where the heart is, and ours will forever belong to Albania.”

But Parubi’s relationship to the country of her family’s origin isn’t so simple.

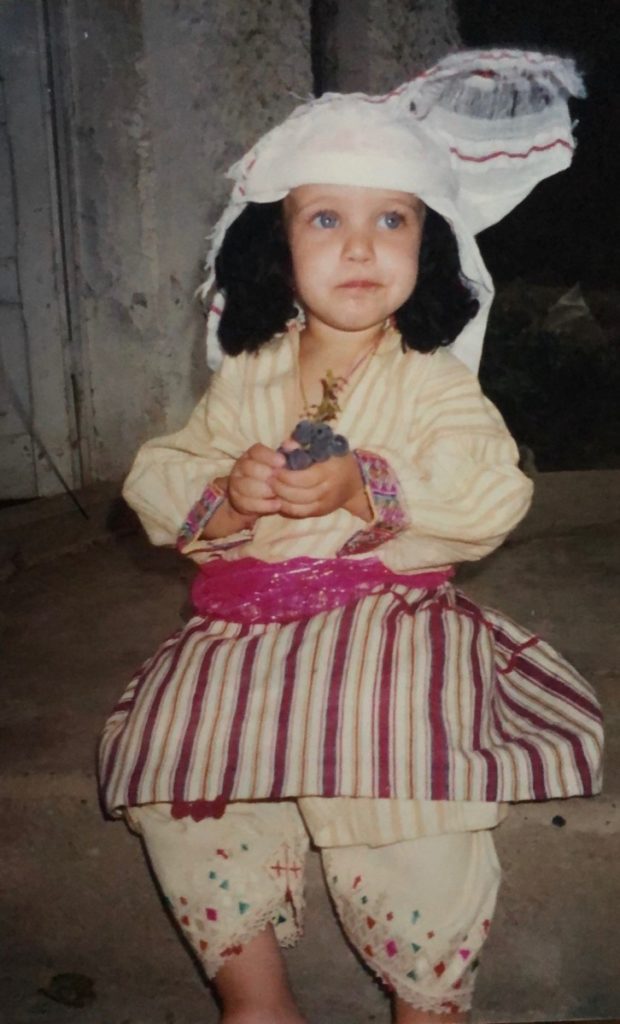

Born just a year after her parents immigrated in 1995, Parubi said that preservation of Albanian identity was important growing up. Throughout her childhood, her parents spoke fondly about their home in Albania, dressed her in traditional clothing and spoke Albanian language in the household to instill the connection to their Balkan homeland, but neither her mother nor her father ever spoke about the hardships that they faced.

“My dad will talk about the happier times or about the future,” said Parubi. “But when it comes the darker stuff, it’s like that time period doesn’t exist.”

Parubi said that the absence of conversation didn’t result in the absence of tension derived from her parents’ past experiences. Her mom has panic attacks. Her dad suffers from depression.

“The older I get, the more I understand what my parents went through, and the more I can make sense of how their experiences affected my childhood,” said Parubi. “As a child, you become what you see. We inherited our parents’ trauma and now we have to make sense of it.”

Denise Hien is a clinical psychologist and researcher who has studied the impact of transgenerational trauma on families for the last 30 years.

“I’ve worked with a lot of individuals who are survivors of genocide or persecution, where the children were suffering from PTSD even though they had never been exposed to the direct trauma,” said Hien. “Absolutely, trauma can be transmitted and carried from one generation to the next.”

According to Hien, there are two major pathways through which trauma can be transmitted. The first is when children are overexposed to the stories that their parents carry.

“If the parent is talking about horrific situations in a way that a child is unable to process, it can be overwhelming and could manifest in anxiousness or depression later one,” said Hien.

The other is when parents are unable to bring words to their experiences and that can result in tension that is also detrimental to a child.

“It’s something you certainly saw in Holocaust survivors,” said Hien. “Many would never speak of what happened. The theory is that that silence then goes on to live an unconscious life that’s transmitted and held by the children of the family.”

Hien said that when there is an unspoken trauma in a family, children can develop related symptoms or disorders and not have an understanding of where they are coming from, much like Parubi’s experience.

“Throughout high school I was dealing with a lot of anxiety and anger that I didn’t understand,” said Parubi. “It wasn’t until I got to college that I was like wow, I can’t let myself become this.”

As Parubi began working to better understand her own battles with mental health, she also began speaking about her experiences with other young Albanians for the first time.

“I thought it was just me because nobody was talking about it, but now I’m realizing there are so many of us,” said Parubi. “I started meeting Albanians that were like me, more modern and wanted to let go and fix these generational traumas. It was really exciting.”

One of the young Albanians she connected with was Ariana Metalia.

“We try to find each other, even if just through social media,” said Parubi. “I have so many friends either from here or back in the motherland that I’ve never actually met, but we have these conversations all the time just because we post about them.”

Together, Metalia and Parubi are working to organize a mental health day for the Albanian community in New York City. Although they haven’t set a date yet, Parubi said that it’s a small step toward normalizing conversations about mental health and inherited trauma.

“My parents never had the resources to address their trauma and get the help that they needed,” said Parubi. “They did the best that they could with what they had, they gave me a future and made sure we had a roof over our head, but I’m realizing that there are things I need to address in myself and things I need to let go of that have damaged me.”

“Now, we’re developing these resources for each other. A lot of us are getting information through education, and what you’re finding now is that the next generation is starting to have these conversations,” said Parubi. “I love standing up for people who are the underdog or who don’t have a voice. I decided I needed to stand up for myself. How can I expect my community to change if I’m not a part of it.”