Eduardo Resendiz woke up in Mexico City to his mother’s whisper. “My son, get your things ready, we are about to leave,” she said seven years ago. “We’re going to meet your dad in the United States.”

The next thing the lanky teen remembered were two grueling bus trips along 700 miles to the northern border, and a frightening trip with a dodgy coyote — a human smuggler — who would paddle the family of three for a fee in a small, inflatable raft over the Rio Grande River along the Texan border.

“We were like zombies, tired, hot and hungry,” said the now 22-year old junior at Lehman College from his apartment on University Avenue in the Bronx. All his life he had heard countless stories about migrants who never made it across.

Resendiz never imagined that seven years later he would still be living in a country where he was not able to work legally, where the threat of deportation is always looming. “I never really had a decision about this,” he said. “I didn’t really know what it meant, I just knew that we had to pack and go.”

But now, the executive order by President Barack Obama that offers deportation deferral to some young undocumented immigrants might dramatically change his future. If the offer of deferral extends to Resendiz, his immigration status would not be permanently resolved, but he would be able to apply for college scholarships. More importantly for him, he would be able to work legally.

That’s if Obama is re-elected on Nov. 6. If the President loses, his opponent, Gov. Mitt Romney has promised to eventually put a halt to the program. The policy could be easily overturned because it was an executive order.

Eduardo Resendiz, 22, is eager for the elections to be over. If Obama wins, he could legally work in America. (JIKA GONZALEZ/The Bronx Ink)

On Aug. 15, the first day that the policy was put into effect, Resendiz was among the thousands of young undocumented immigrants who lined up around schools, churches and consulates waiting to fill out applications for deferred action.

But unlike the thousands of hopefuls who jumped at the chance to change their immigration status, Resendiz’ application is sitting in a drawer, still waiting for his own signature. He is waiting to file his paperwork until he knows the result of next week’s presidential election.

Deferred action for childhood arrivals, referred to as DACA, is meant for undocumented immigrants who were brought to the country illegally as children and teens. Applicants must fit specific criteria. They must prove that they were brought in to the U.S. before their 16th birthday and be under 31. They must be in school, have a high school diploma or equivalent. And they must have a clean criminal record.

Some legal experts understand the fears, but believe that simply submitting papers will probably not increase the possibility of deportation. “There are risks involved, but deportation is highly unlikely,” said Maaria Mahmood, a third-year law student at Brooklyn Law School, who assisted Eduardo with the application. “The government is saying that they won’t go after the families, but you have to understand that you are giving all your information to the government.”

While the president’s offer of temporary amnesty is promising, Resendiz remains skeptical. The politically divisive climate has led to anxiety, and while Republican candidate Mitt Romney has publicly said that he won’t reverse approvals, he has also stated that he will halt the program as soon as he’s in office. “I don’t want to put my family in danger,” said Resendiz, noting that his mother, father and sister are also undocumented. “I think it’s too risky knowing that Romney could reverse the decision.”

Applicants are screened by the U.S. Office of Homeland Security. Those who meet the criteria will be allowed to remain in the United States and work legally for two years. As the policy stands now, they will be able to re-apply after the initial two-year deferral passes.

With deportations at a record high, averaging 400,000 per year under Obama’s presidency, the new policy could benefit up to 1.7 million of the 4.4 million unauthorized immigrants, according to the Pew Research Center.

From 2005 to 2010 the department of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which is overseen by Homeland Security, apprehended over 34,000 New Yorkers, according to a study published last July by the Immigrants Rights Clinic of New York University School of Law. Apprehensions have increased 60 percent since 2006, averaging at 7417 each year. The report also noted that 91 percent of those detained in New York are deported.

Resendiz fears that if he does not get approved, or if the policy is reversed, he could be putting himself and his family at risk of deportation. “I’m afraid of being separated from my family, afraid of having to go back to Mexico and having to start all over again,” he said.

Seven years after arriving to the United States, diplomas awarded for his academic performance line the walls of the young man’s room. He dreams of being a music teacher, and of being to others what his mentors have been to him.

“All the teachers remember him, even the principal,” said Ian Mustich, Resendiz’ former music teacher at New World High School, the school where Resendiz landed when he arrived as a teen to New York.

At the time he found walking around New York City was “unreal,” and settling into a new life in the Bronx, tough. “You don’t know how to get around, you don’t know the language,” said Eduardo. “You feel like you don’t belong.”

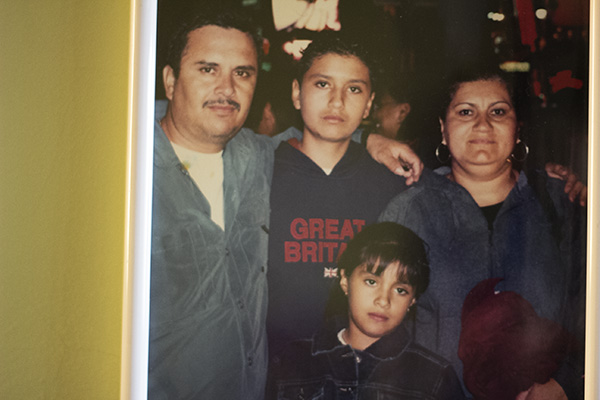

When Resendiz arrived to the U.S. with his mother and his 7-year old sister, his father had already been living in the Bronx for three years. His father had left Mexico in 2002 when Eduardo was only 12 years old. He had come to make more money as a construction worker and support his family back home.

A photograph of the Resendiz family when Eduardo, his mother and sister first arrived to the United States. (JIKA GONZALEZ/The Bronx Ink)

Three years later, Resendiz’ mother decided that it was time to reunite her family. She felt that her children needed a father. “They needed to recognize who he was, they needed to know who was putting food on the table,” she said in Spanish.

The first day as a high school freshman was rough. Resendiz, who said he had always been a straight A student, found himself frustrated and unable to communicate. “All my classes were in English and I didn’t even know how to ask for permission to drink water or go to the bathroom,” he recalled. “I got home and I told my parents that I didn’t want to go back.”

Resendiz was disillusioned, but his parents pushed him to keep trying. Six months later he finally began to adapt. Mustich, who taught at the school for eight years, described Eduardo as an outstanding student. Three years after graduation the principal still has a picture of Eduardo and his friends on his desk.

Today, Resendiz feels at home. He identifies as both Mexican and American, but feels he cannot grow lasting roots in the U.S. as long as he remains undocumented. “I live here, I speak the language, I feel accepted,” he said.

As of Sept. 14, over 32,000 undocumented immigrants have applied for the Obama Administration’s deferred action. So far, 29 applicants have been approved, according to U.S. Immigration and Customs Services.

“The chances that Eduardo won’t be granted deferred action are slim to none,” said Thanu Yakupitiyage, a communications associate at The New York Immigration Coalition. “He is a highly qualified candidate.” She calculates that once Eduardo sends his application, he would have the result in roughly six months time.

Yakupitiyage, who got to know Resendiz when he was granted a college scholarship through the coalition in 2012, was with Resendiz when he put his application materials together. There were hundreds of people inside and out of lower Manhattan’s St. Mary’s church. Resendiz gathered his documents quickly but did not leave when he was done, remembered Yakupitiyage. He stayed and offered his help to other deferred action hopefuls throughout the day. “He is very talented, very smart and very active in his community,” she said.

Pending the results of next week’s election, Resendiz will be ready to file his paperwork. “It’s necessary to have peace of mind and not have the fear of deportation always present,” he said. He wants to make his parents proud, graduate from college and get a master’s degree. “But when you’re not stable in a country, you can’t do much, you can’t put roots down.”

Eduardo Resendiz, 22, a music major at Lehman College: “When you’re not stable in a country, you can’t do much, you can’t put roots down.” (JIKA GONZALEZ/The Bronx Ink)