A green photo album rests on her open hands. Inside, there’s a collection of carefully photographed flower arrangements.

“I love plants, sometimes I feel like they’re talking to me,” said Carolina Bernal, 54, a Mexican immigrant who has been running her own flower shop in the southeast Bronx for two years. Surrounding herself with flowers has become a safe haven for her, having left everything she ever cherished behind.

Bernal is one of millions of Mexican immigrants who have risked their lives by crossing the border to the United States, trading their homes and families for an uncertain but promising future. Despite paying taxes and contributing to the U.S. economy, this group of undocumented immigrants lives in fear of deportation in an era of Donald Trump.

Life in the barrio

Bernal’s story as a hard worker starts when her life as a student came to an abrupt and unexpected end almost 40 years ago. Born and raised in Santa Cruz Meyehualco — a poor neighborhood in eastern Mexico City — she was the second daughter in a family of nine children.

Her mother kept pigs, geese, turkeys, and chickens to feed the family. Her stepfather provided for everything else.

When Bernal turned 17, her stepfather died, taking her childhood with him. He died of a liver disease. “He passed away from getting so terribly mad,” she said, holding her hands together, shifting her gaze to the floor.

As one of the oldest children, Bernal had to help her stay-at-home mother; she started looking for a job as an accountant’s assistant. The first man she interviewed with tried to sexually abuse her, so instead she took a low-paying shift in a plastic factory situated in the industrial belt that surrounds Mexico City.

Her life as a working high school student did not last; Bernal had to drop out of school to work both night and day shifts. She promised herself she’d only quit school for one year while things got back on track. But she ended up working for the company, Plásticos y Reparaciones de Monterrey, for the next 15 years.

Bernal began as a floor employee in a plastic injection plant. She had to work three shifts a day to buy one pair of shoes. It was 1982, she was barely 19, and Mexico was experiencing one of its most notorious economic crises.

As time went by, between one shift and the other, injecting plastic day in and day out, she slowly began to exercise leadership among the employees.

Ten years later, Bernal had worked her way up to quality control manager. She was in charge of making sure their main client, the rum manufacturer Bacardi, was happy with the product.

“At that time, I was negotiating millions of pesos. My signature carried weight,” said Bernal, as she sat on a plastic chair in the corner of her shop filled with flowers. “You know, engineers and businessmen would look at me and say ‘now, this woman is a motherfucker’ because I knew my business and delivered impeccable results”.

By this time, Bernal was 30 years old, and a single mother to a 5-year-old son. That’s when she married, had a daughter, and her life took a dark turn.

“A smart woman can go as far as she wants, until she falls in love,” said Bernal holding her now 23-year-old daughter’s hand behind the shop counter.

Her husband, she said, was jealous and possessive. She had a miscarriage and quit her job. Just like that, 15 years of her life came to another abrupt end.

Her daughter Gaby was born when she was still battling postpartum depression from her previous pregnancy. Soon after, she got a divorce. Bernal went back to work for Bacardi, but her responsibilities as a single mother of two children were overwhelming.

When she discovered the public school her children attended in Mexico City was illegally charging her a fee and putting her children to work mopping and scrubbing floors, she placed her kids in a private Catholic school.

In order to pay for the exorbitant tuition, Bernal moved in with her mother, went back to school, and started a business making school uniforms.

Five years later, her business collapsed when she lost her car in a crash and could no longer deliver the uniforms. With piling debts and no better options, she decided to cross the border into the U.S., making her way to 116th Street in Harlem. After sleeping in a church for a few nights, she moved to the Bronx.

That’s how, nine years ago, a 43-year-old Carolina Bernal crossed the Mexico-U.S. border through the dessert under a blazing sun. She was the oldest immigrant and only woman in the group of young men she was traveling with. Exhausted, one day she decided she couldn’t keep going, and asked to be left behind while lying on a hot black rock.

The boys wouldn’t have it. “Vámonos Doña Carolina”, said Bernal quoting her travel companions when they lifted her up from the rock. “That’s when people started calling me Doña”, she explained in Spanish, making it clear that her nickname was a sign of respect, due to her age.

Doña Carolina then became one of the 11.3 millions of immigrants without proper paperwork in the U.S. as of 2015, according to the PEW Research Center. Even if Mexican immigration has been decreasing since 2007, 49% of all undocumented immigrants are still Mexican; the majority of them work in service sector jobs, like flower design.

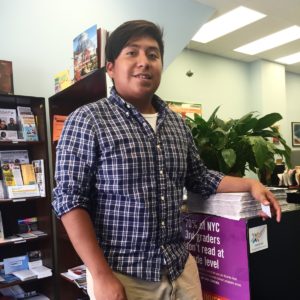

An unassuming entrepreneur

At age 43, and still without a high school degree, Doña Carolina found herself working as a nanny, a private cook, and a kitchen aid in several Mexican restaurants.

It was in 2007 after one of her long night shifts at the Pancho Villa restaurant that she took a cab home because she was too tired to navigate the subway. A drunk driver hit the taxi, and Doña Carolina was badly injured. She sued and was given a small settlement of $5,000, which she used to open Carolina Flower Shop.

Unable to work long shifts in the kitchen because of her new disabling column lesion, she looked for something that didn’t require as much physical work. Selling flowers was her solution.

Before owning her store, Doña Carolina sold flowers out of a bucket on the sidewalk. She stationed her mobile business in front of a small shop on Westchester Ave., in the shadow of the No. 6 line. But her life as a hawker only lasted a couple of months. Just when the flowers started freezing in the winter cold, the tenant of the shop moved out. Doña Carolina took the opportunity and used her savings as a down payment for the rent.

Doña Carolina had managed to secure a commercial space and open her own small business, but she didn’t know the first thing about actually arranging flowers. She taught herself quickly, using YouTube videos and practicing with fresh stems. Her customer service experience in Mexico prepared her for serving the clients.

Today, Carolina Flower Shop, a couple of blocks north of the St Lawrence Ave. subway station, brims with bamboo bunches in different-sized pots and multicolored alstroemerias resting in buckets of water inside the fridge. She has good-luck pink mini cactuses sitting sturdily next to elegant orchids.

The green plants with leaves reaching up next to the wall are believed to bring prosperity to new businesses. Inside the fridge, carnations look like pompons shoved against each other and gerberas explode in a rainbow of colors. In the corner, white lily buds are about to bloom.

Back in early 2014, when Doña Carolina’s enterprise was on the pavement, she used to get her flowers from warehouses like Select Roses in Hunts Point. Those big depots have container-sized refrigerators where the flowers are stacked in boxes. The warehouse owners import a bunch of 25 roses for $2.

Nowadays, Doña Carolina gets her flowers from a Korean deliveryman who goes directly to the airport customs office and delivers boxes of flowers twice a week to the doorstep of Carolina Flower Shop. The Korean middleman sells the same 25-rose bouquet for $17 to the florists.

Doña Carolina buys each rose at 60 cents more than its original value. She compensates for the cost of shipment and delivery by producing creative merchandise like flower arrangements and bouquets.

Each bouquet has about 12 roses, adorned with cheaper flowers used as filling, and various green leaves of different shades and shapes. She sells the bouquets — perkily poised in their cellophane wrapping — starting at $70.

Creating value is not the only challenge faced by Mexican shop owners like Doña Carolina. She’s also had to learn how to revive a flower that has been kept in refrigeration for months.

Withered flowers are easily identified; their twigs don’t snap when broken, their leaves are pale and opaque, and their buds are often stuck in the opening phase, like a teenager in arrested development. In order to bring them back to life, Carolina slices their stems diagonally, making it easier for the plant to absorb water.

According to the Department of Labor, there were 2,980 floral designers in New York in 2015, the second most in any state after California. Florists like Bernal earn an average hourly wage of $14.49 and an approximately $30,140 a year. Floral designers in New York are not among the best paid in the industry. In nearby Connecticut, florists make more than $36,000 a year, on average.

Soon after her business opened, Doña Carolina’s daughter joined the family in the Bronx. With a college degree and her mother’s earnings, Gaby came to New York City, and now helps her mom run the flower shop. Gaby is in charge of finances, social media accounts, English speaking costumers and theme party paraphernalia. Doña Carolina manages everything else.

“In spite of all the problems she had, my mom is an independent woman who never needed a man to succeed,” said her daughter, Gaby.

When her daughter finally made it to the U.S., she hadn’t seen her mother in seven years. “When she saw me here, she found a grown woman instead of the little her she had left behind.” The two make a good team, they say. Sometimes they fight, sometimes they laugh, but they always support each other.

“I have to rinse her tears and tell her that she’s wrong, just as she does with me,” Gaby said.

With no previous experience in the flower business, Doña Carolina’s biggest asset is customer service. She figures out ways to accommodate her clients, like when the employees of a deli off Grand Concourse needed a bouquet delivered on Sept. 29. Doña Carolina charged $15 for delivery and then paid for her daughter to take a cab to the deli, tucked behind Bronx Criminal Court. The flowers were for a woman who was forced to retire after nine years because of health problems. Holding the bouquet with her arthritic fingers, the woman said she loved the red and white arrangement.

In late September, Feliciana Danielle popped into Carolina Flower Shop with her husband. They were looking for a centerpiece for a black and gold themed party. Doña Carolina quickly sprayed a couple of green branches with gold and black spray paint and gave Danielle time to think.

After the $90 order was placed, Danielle said she was a returning customer. “I had been here years ago, when I bought the flower arrangements for my wedding.” She came back, knowing Bernal would know how to put together an arrangement that met all her needs.

Doña Carolina opens her shop every day at 8 a.m. After all her ordeals, she won’t stop working until she achieves her final dreams. Her next challenges are obtaining legal residency, getting a car to expand her business, and buying a small house in which she can spend her last days.

“I’ve been run over once and again,” Doña Carolina said. “But no matter what comes my way, I keep getting up.”