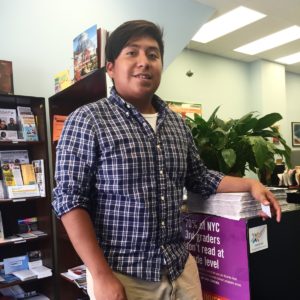

“How can I help you?” asked Israel Sanchez, 20, at Ritchie Torres’ City Council office in the Bronx. He had a calm presence and professional tone, wore a button-down checkered shirt, and spoke with no accent. He was caught at the reception desk with no reference files in front of him but was still able to explain in detail the status of Latino immigrants in the neighborhood. He gave all reference contacts, including email addresses, accurately from memory.

It’s a topic Sanchez knows well. His family is not only part of the immigrant community in Fordham but among the most vulnerable.

“My parents and I live off the book. We pay taxes but the country doesn’t recognize us as legal residents,” he said. “On one hand, you love this country, but on the other, your life is really difficult.”

Meanwhile, a Latino family of ten crowded into the city council office, taking over the reception area that only tightly fits five chairs. Three adults and a flock of children, whose ages varied from toddler to early teen, all spoke Spanish to each other. The woman with the youngest on her lap shook her head with an awkward smile when she was asked if she spoke English. They needed Sanchez to help them communicate.

“People think things in elections won’t affect your lives. But it’s because of what Obama did, I was able to be here and do what I do,” he said, referring to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals – a presidential executive action that President Trump would rescind and President Clinton would defend. The Sanchez family, who cannot vote in the elections, hope the voters will make the right choice for them.

Protection against Deportation

Sanchez was brought to the United States from Mexico when he was two years old. His parents took him to climb over thorny fences at the Mexico-California border, and flew to New York. He qualifies for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the executive action initiated by President Obama in June 2012. The action has temporarily protected more than 700,000 immigrants from deportation, 66.6 percent of whom are Mexicans. These immigrants, who are eligible for the executive action and are called the Dreamers, were brought to the United States as children and have made the country their home. Although the executive action does not offer a legal path to citizenship, the Dreamers approved are given temporary work permits.

Immediately after the policy announcement by President Obama, Sanchez applied for the executive action, eager to be able to work legally. He researched the application process, gathered all the legal documents, and submitted the application himself.

Sanchez is temporarily relieved that there is finally a policy that protects immigrants without legal permission like him. “I guess I would be more concerned to meet you if I’m not protected by DACA,” Sanchez said. “The concern is always at the back of our heads.”

His concern does not come from nowhere. The Obama administration has deported more immigrants than any previous president, and the number has been steadily increasing year by year. Although New York City is not among the cities with the top number of deportations, Sanchez and his family are still at risk every day. He deliberately avoids any unlawful activity – things that would be destructive but less devastating for American citizens to be caught doing, such as possession marijuana or working at an illegal business. His uncle’s experience taught the family a lesson.

Hoping to work and earn his living, Sanchez’s uncle landed a job at a company that manufactured counterfeit Nike shoes, where many of the workers were undocumented. Later, the company was reported to the police and had to shut down. Sanchez’s uncle was arrested, and his status was exposed, along with the other immigrant workers who did not have work permit. As a result, he was deported and sent back to Mexico in 2012, after living 20 years in the United States.

The Identity

Although Sanchez’s parents have always told him to be extra careful, he was on TV once with Julissa Arce, an author and advocate for Mexican immigrants. In facing the topic, Sanchez never backs down, and his spine is always straight. After Sanchez received protection against deportation, he has become more active in speaking for immigrants like him. Margaret Calmer, Sanchez’s girlfriend since high school, recalled that their high school friends who used to joke about him being Mexican respected him more after knowing the hardships he has faced.

Without a second of hesitation, Sanchez identifies himself as an American. He enjoys Mexican food and music, but since his first memory, he has never stepped out of the country. He’s had an American education and upholds American values like independence and protection for human rights. He wants a career in government to make better policies for immigrants like him.

In order to achieve his goal, Sanchez interned at the city council office while he was a full-time college student and working at Staples for tuitions and expense. “He always works extra hard to prove that he deserves to be here,” Calmer said.

But he becomes frustrated when his identity clashes with how other people see him. “I think I’m an American, but it’s difficult to claim, since I’m not a citizen,” said Sanchez. He finds many people address him first in Spanish. He was once stopped on his way to Boston because his truck had a headlight out, but the police officers asked if he spoke English and searched his truck for drugs for half an hour. After private middle school, he was accepted to a private boarding high school in Virginia, but this dream school revoked the admission decision after the family visited the campus. The school told him that the revocation was a result of his legal status, but he speculated the real reason being that other students’ parents did not like his Mexican origin.

“I was the only Mexican kid. It was very difficult for people like me to go to a school with bunch of rich kids. You kinda feel you are out of the place” Sanchez said. “You kinda expected things like this to happen, but you didn’t think it would actually happen.”

The school admission office, on the other hand, stated that the school would verify the legal status of any applicant. The director of admission did not recall any incident of revocation of admission offer since 2006.

Sanchez’s road to the American Dream demands more efforts than his American peers. He says his Mexican parents hardly know how American society works, and, along with his two younger brothers, rely heavily on him to navigate their lives. Sanchez in many ways has become the third parent of the family. From credit cards to car insurance to college applications and internships, Sanchez has learned it all by himself.

“I have to explain little things like internships to my parents. Sometimes it’s frustrating,” he said.

Unseen Future

Because Sanchez’s temporary status comes from a presidential executive action, the next president, either Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton, could revoke the policy. People like Sanchez would no longer be able to work legally and would not be protected from deportations. It’s his worst nightmare.

He is afraid that the new president will drop the policy, and the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service will report him to law enforcement units for deportations. “They know me now. They know I’m here,” he said.

Sanchez is graduating from Baruch College in two years. He has two scholarships that cover all his tuition, putting no financial burden on his family. But his political commitment to make immigrants’ lives better would be more promising if he were born in the country and had a U.S. passport.

“He’s just normal, like the rest of us. He jokes around and he enjoys his life. But until something changes, there’s always going to be legal status hanging over his mind preventing him from living an entirely normal life,” Calmer said. “All he wants is a normal life.”

“I can never be the President. That’s one thing,” half-joked Sanchez. But whoever does become president can determine whether he can become officially American.