About 40 middle school children—all but one from Bangladeshi immigrant families in the Bronx—sat quietly inside a stark classroom at Khan’s Tutorial in Parkchester on a Sunday afternoon in September. Barely audible from the upstairs classroom were the sounds of children playing at a nearby park as the 12 and 13-year-olds reviewed fractions, greatest common factors and least common multiples.

Eighth grader Rafsan Zaman, with the beginnings of a moustache and a mouthful of braces, reviewed again and again the one math problem he missed on a practice test from that morning. Rafsan’s name was up on the Khan’s Tutorial room whiteboard as it had been nearly every week. It meant that he was the top scorer on the 100-question practice exam for the specialized high school admissions test, known as the SHSAT, the all important gateway exam into the city’s eight legendary, elite public high schools. It was set to be given on October 24 and 25–in just two weeks.

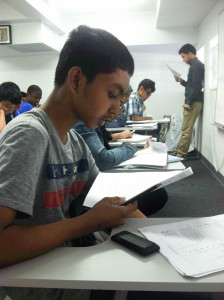

Eighth grader Rafsan Zaman studies nearly 15 hours a week for the specialized high school exam he will take at the end of the month.

Still, for Rafsan, one wrong answer meant there was room for improvement. Parents said they can spend up to $4,000 for the year-long tutoring program. Their hopes for their children’s futures depend on a high score.

“Every time the score comes back it gives me more information of what I need to study,” said Rafsan, tightly clutching an algebra practice book under his arm. The eighth grader expects to get into Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan, considered the best of the best of the elite schools that include Bronx Science, Brooklyn Tech and LaGuardia School of the Arts. Admissions decisions are based solely on results from the highly competitive SHSAT, a requirement that is currently up for debate in the state legislature.

“It sets the way for college and career,” Rafsan said.

Three rows behind Rafsan sat Rahat Mahbub, also an eighth grader, but with a younger face and gentler demeanor. Rahat worried that his reading comprehension scores would not be good enough. His mother, Taamina Mahbub, enrolled him in Khan’s SHSAT prep program in June of 2013. She feels almost the same pressure as her son, and urges him to keep studying. “The process is stressful and the culture is competitive,” Taamina Mahbub said. “I am really nervous—usually the parent is more nervous than the child.”

For the last two decades, this private SHSAT tutoring company has successfully targeted the city’s growing Bangladeshi immigrant community. Khan’s Tutorial, a 20-year-old institution begun in Queens, recently set up its second center in the Bronx, following the Bangladeshi immigrant migration from Jackson Heights to Parkchester that began in the 1990s. The website advertises prices at $15 per hour. Parents said they pay as much as $4,000 for their children to attend tutoring nearly two years before the exam, hoping a high score will help guarantee placement in a good university down the road.

Since its founding in 1994, Khan’s has sent 1,400 students to specialized high schools. Some students come two weeks prior to the exam for tutoring, some start as early as the sixth grade. The company’s administrators recommend that students prepare for the exam at least one year in advance. “For South Asians or Asian Americans, the SHSAT has been the common path to pursue in our culture,” said Sami Raab, director of Khan’s Tutorial in Jamaica Queens. “You see testing as important and that carries over to first generation children.”

Khan’s Tutorial, a prep center for standardized tests like the SHSAT, opened a second location in the Bronx this year to accommodate the growing Bangladeshi community in Parkchester.

For students who are well prepped, scoring high on the SHSAT is possible, but for those who can’t afford tutoring programs, or don’t know about the test at all, access to specialized high schools remains out of reach. Bronx students have historically ranked at the bottom in the city in terms of the number of children who take the test, and who score high enough to be considered for admission. Although the city provides free tutorials, such as the DREAM Specialized High School Institute (SHSI)—a rigorous 22-month program offered to sixth graders with high test scores and financial need—some feel that more needs to be done. Many, including Mayor Bill de Blasio, believe that the single test criterion is unjust and leads to student bodies in the elite schools that do not represent the public school population.

Last year, 375 Latino and 243 African American public middle school students were offered admission at the eight specialized high schools, compared with 2,601 Asian and 1,256 white students; this in a system where 72 percent of the public school students are black and Latino. After a complaint lodged by the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and the increased controversy over the schools’ one test admission process, Mayor de Blasio proposed a bill in June that would allow for criteria such as attendance and grade point average to be considered as well. Those in favor of the bill claim the legislation would give students without extended tutoring and prep, a better shot at specialized high schools.

Assembly member Luis Sepulveda who represents Castle Hill and Parkchester, is a co sponsor on the bill. He called the 12 percent of African American and Latino students at the elite three specialized high schools—Stuyvesant, Brooklyn Tech and Bronx Science “dismal” and “unacceptable.”

“Anyone can have a bad day and do poorly on a test,” Sepulveda said. “Schools have to look at other criteria. It’s not solely about your education, it’s about your involvement in your community.”

The day after de Blasio proposed the bill last June, coalitions in favor of the test formed in protest. Don’t Abolish The SHSAT and CoalitionEdu, as well as parent and alumni associations from the specialized schools, argued that the test did not cause a lack of diversity in the high schools. Instead, they said, the fault lay with a school system that failed to prepare more diverse students to pass it. Don’t Abolish The SHSAT has collected 4,198 signatures through its website and CoalitionEdu offers politicians’ contact information, urging parents and students to get involved. These groups claim the school district’s lack of communication about the test leaves students from low socioeconomic backgrounds out of the loop until it’s too late to study.

“The overall issue is failing K through Sixth grade and middle school systems throughout New York City,” said the head of Khan’s Tutorial, Ivan Khan. “By proposing a more holistic approach, wealthier families will have better access to more subjective resources. We strongly feel that those should be explored further rather than changing the criteria.”

While Khan’s Tutorial addresses the bill from the corporate level, tutors keep the issue at bay during weekend test prep. Rafsan and Rahat had two more Saturday classes before they took take the two-hour test alongside 27,000 other eighth graders on October 25 or 26.

“It’s just a test,” said Rahat, with uncommon calmness. “I know it’s the most convenient way, but one Saturday moment doesn’t determine everything.” Rahat’s mother believes an essay or report card should be included. His stay-at-home mom has seen too many bright students miss out on the opportunity to go to a specialized high school because of the single criterion. “It should change,” Mahbub said. “One test is not fair. One or two points and you have to go to another school.”

Still, tensions are high as the test date approaches. It may abate after the test is given, but will likely return in February when the results are announced. Middle schools, tutoring centers and the Parkchester neighborhood unofficially referred to as Bangla Bazaar, will buzz with the news of who got in where. And who didn’t.

Mohammad Rahman, a 14-year-old from Castle Hill, remembers the day last February when his SHSAT results came back. Fifteen months of prep at Khan’s in Castle Hill and countless hours studying at home were for naught—Mohammad’s scores weren’t high enough to get accepted. He would not join his brother at a specialized high school. “I felt to an extent ashamed I didn’t get in,” Mohammad said. “My mom felt I should follow in [my brother’s] footsteps.” Now a freshman at Manhattan Center for Math and Science, Mohammad thinks maybe the single test process isn’t fair. “People just study the test format,” he said.

Wasi Choudhury writes the top scoring students’ names on the whiteboard as incentive for all of the students to study harder. “Everyone’s goal is to get on that list,” he said.

Photocopies of practice tests fill Rafsan’s backpack. He estimates he has taken over 20 by now. Because Khan’s Tutorial is known for giving diagnostic tests that are more difficult than the actual SHSAT, Rafsan is hopeful. “If you can get a 95 or a 96 on these tests, you can definitely get into a specialized high school,” he said.

Rafsan’s tutor at Khan’s Tutorial, Wasi Choudhury, will continue to write the top scorers’ names on the whiteboard for the class to see. There are only 2,500 seats in the top three specialized high schools and students know their competition is each other.

“Everyone’s goal is to get on that list,” Choudhury said. “It pushes them to get up there.” Choudhury, a student at New York University and an alumnus of Bronx Science said Rafsan has a good shot of “going specialized,” though tutors can never know for sure. “Stress ruins it for a lot of students,” Choudhury said. “There were kids that we said were sure to get in and failed the test.”

Rahat lives a few blocks away from Khan’s center in Parkchester and looks forward to the coming weeks when he doesn’t have to come sit for four hours on the weekends. This summer his family will be able to visit Bangladesh—a vacation forgone last summer due to his tutoring schedule. In November, Rahat plans to apply to private schools, in case the test day doesn’t go as planned.

But life will be good, he said, if he scores high enough on the test. “I’m going to play six hours a day. Nothing will matter because you got into a specialized high school.”