The tiny waiting room of Dr. Andrea Littleton’s Bronx office was overflowing by the time she arrived in the late morning. Some patients sat in stony determination while others paced impatiently in the hallway — clawed by addiction and anxious for the relief that Littleton could provide. One dozed, slouched in his chair beside the inner door that leads to the claustrophobic medical office where, twice a week, Littleton prescribes buprenorphine to opioid addicted patients.

Littleton has worked for 15 years at Care For The Homeless, a non-profit medical center that provides medicine-assisted treatment for the homeless who suffer from opioid addiction. Medicine-assisted treatment is considered the “gold standard” for opioid use disorder, and the medications used are typically either methadone or buprenorphine (also known as Suboxone).

Littleton’s office, situated in Hunts Point in the Bronx, is at perhaps the very heart of New York’s opioid epidemic. In 2018, the overdose deaths per capita in Hunts Point was over 2.5 times the city-wide average, according to a 2019 report from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Only Staten Island ranks above the Bronx in terms of number of opioid deaths per capita. However, treatment in the two boroughs looks very different.

“Even though both [Staten Island and the Bronx] are epicenters of the opioid epidemic,” said Littleton. “There are far more [buprenorphine] prescriptions being written in Staten Island, but not necessarily more providers.”

A 2018 research report confirms Littleton’s observation: patients in Staten Island receive buprenorphine 3.6 times more frequently than those in the Bronx. Patients in the Bronx are, likewise, 3.2 times more likely to receive methadone. All this while the Bronx has nearly three times as many physicians who are able to prescribe buprenorphine, according to federal data.

The difference between the two treatments is meaningful. Methadone must be administered under supervision in specialized clinics. Buprenorphine, on the other hand, can be prescribed by certified doctors and can be self-administered in the form of oral tablets.

“[Buprenorphine] certainly offers more freedom and flexibility,” said Littleton. Some patients refer to methadone treatment as “liquid nails,” she said. “They can’t go anywhere else or have a job or travel even because they have to be there every day.”

Having to show up at the clinic every day to receive treatment is not only a burden on methadone patients. The clinic itself can be stressful. “There is also a lot of stigma,” said Littletone. “People know where [the clinics] are, they don’t feel safe there. And it’s triggering because there might be someone selling right there in the waiting room or right outside the door.”

Finally, the medication itself makes a difference. Buprenorphine lacks some of the negative side-effects that methadone is notorious for. On Buprenorphine, patients “can go about their day feeling normal, they don’t feel high, they don’t feel loopy, they just feel normal,” Littleton added. “Where as a lot of people on methadone feel high, they can’t think clearly, they feel like they can’t maintain their normal activities.”

In 2018, Canadian researchers published guidelines recommending buprenorphine as the preferred first-line treatment for opioid addiction, only switching to methadone for patients who respond poorly to buprenorphine or who express a strong preference.

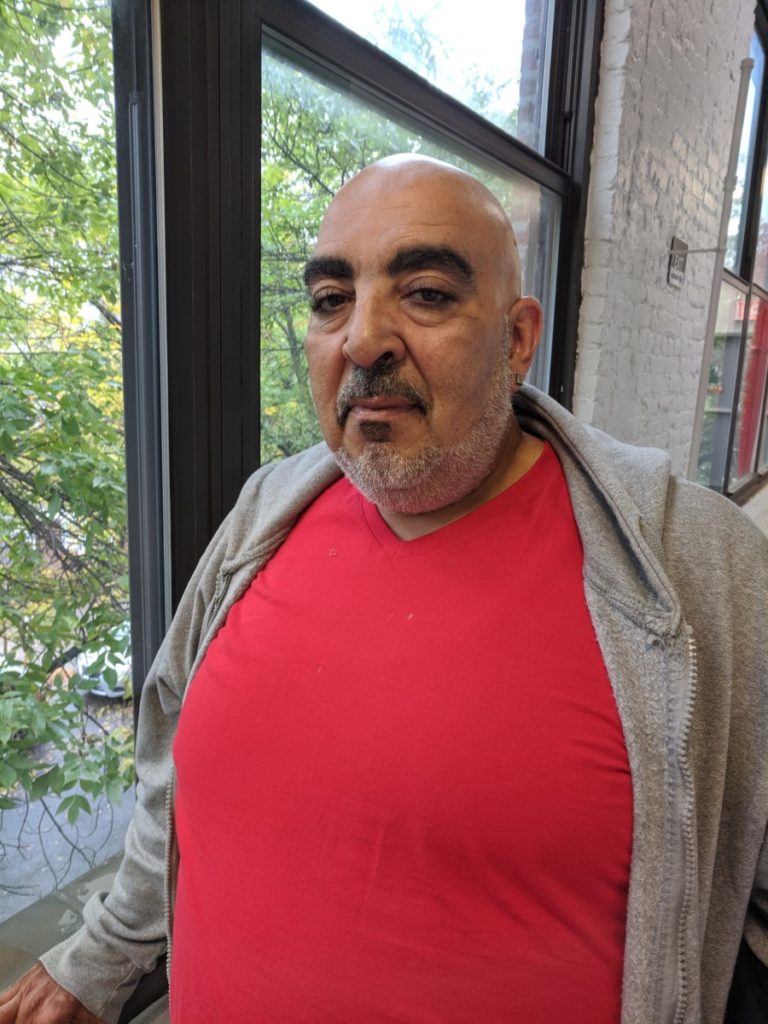

Salvador, who asked that his last name not be used, is a big man with tired eyes and a tidy grey beard. He is one of those patients who depends on the buprenorphine he gets from Littleton every week.

“When I have these,” he said holding a zip-lock bag containing week’s supply of individually-packaged pills, “I don’t even think about [heroin]. But without them, I have to use.”

But that reliance on Littleton can spell disaster if she is not available.

Salvador had been clean for nearly two months, he said. But, when Littleton had been away the prior week, he hadn’t been able to find another prescriber. Salvador had gone back to heroin to satisfy his cravings.

“You abandoned me,” Salvador sulked jokingly. But the damage done is no laughing matter.

Now, Salvador will have to endure the unpleasant, and potentially dangerous, process of reinitiating his treatment. Buprenorphine includes naloxone (the active drug in Narcan) which can precipitate withdrawl if patients start treatment too soon after using. Complications from withdrawl, including dizziness and asphyxiation can be severe. He will have to start the first stages of withdrawl from the three baggies of heroin he snorted that morning before he can take his first pill.

Despite the success of buprenorphine, getting access to treatment still remains a problem for many Bronx residents. In February 2019, the New York State Department of Health released new guidelines encouraging SAMHSA-approved doctors to “start prescribing buprenorphine, and if already prescribing to increase the number of patients under care.”

But the question remains, why do these two boroughs, facing the same crisis receive such different modalities of treatment?

From the start, buprenorphine treatment catered to affluent white patients who did not want to be associated with the stigma of receiving treatment at methadone clinics.

“In the case of opioids,” writes Dr. Helena Hansen, Associate Professor of Psychiatry at NYU Langone. “Addiction treatment itself is being selectively pharmaceuticalized in ways that preserve a protected space for White opioid users.”

Buprenorphine was developed in 1966, but failed at catch on until it’s resurgence 30 years later, which, argues Hansen, coincides with the rise of opioid use in white communities. When buprenorphine was legalized as a treatment for opioid addiction, in the 2000 Drug Addiction Treatment Act (DATA 2000), a group of lawmakers who opposed the DATA 2000 bill foresaw that it would “consign ‘hard core’ users to the existing and widely recognized as failed system.”

Sure enough, as the opioid epidemic exploded in in New York City, buprenorphine was increasingly available only to those who could afford private insurance. Between 2009 and 2016, the number of buprenorphine prescriptions on private insurance increased by over 4.5 times, while the number on medicaid fell nearly by half. In 2016, over three-quarters of buprenorphine prescriptions were paid for by private insurance.

While the city’s $60 million HealingNYC initiative has shown modest success in reducing the number of overdoses city-wide and increasing buprenorphine prescriptions, it hasn’t been enough in the Bronx, where opioid deaths continue to increase.

“It’s supply and demand,” said Dr. Tiffany Lu, Medical Director of the Montefiore Buprenorphine Treatment Network. “The Bronx does not have enough capacity because it historically had the burden of the disease.”

And while money for outreach and education programs are essential, the greatest hurdle in the Bronx is finding physicians like Littleton and Lu who are able and willing to prescribe buprenorphine.

Under DATA 2000, prescribers are required to obtain special wavers to even be allowed to prescribe the treatment. Completing the requirements can be an arduous burden to already-overextended care providers. Doctors are required to attend eight hours of training and clinicians (including nurse practitioners and physicians assistants) are required to take 24 hours of training.

However, once a physician has a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, they are only allowed to treat 30 patients in their first year. This cap increases to 100 and 275 patients in their second and third year, but the cap still contributes to the shortage of access to buprenorphine prescribers, according to a letter by the New York State Department of Health.

Some physicians question the need for a waiver at all. “[Buprenorphine is] a schedule III drug,” said Littleton. “It’s less addicting substance than opiates, but prescribers are able to provide [opiates] at will without training.”

A bipartisan bill, the Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment Act of 2019, has been introduced to both the House and Senate. The bill would allow physicians to prescribe buprenorphine without a DEA waiver.

Still, even some physicians who interact with opioid-addicted patients may be reticent to start buprenorphine treatment.

Rikin Shah, Chief Resident at St. Barnabas Hospital in the Bronx, is not waivered to prescribe buprenorphine. In the emergency department, where he typically encounters such patients, initiating buprenorphine treatment would require counseling and monitoring, and in a 200-bed room, where other patients require attention, he doesn’t feel that starting new medication is a good idea.

“We may not be able to monitor how they are doing on the medication, whether they need changes in doses, or if they are having any adverse drug/side effects,” Shah wrote in an email. “This is dangerous for our patients.”

Emergency departments are not the appropriate venue for starting addiction treatment, Shah continued, and promoting them as such might lead to an abuse of their resources.

“We need to optimize our resources to taking care of the sickest patients and to those who are at risk of losing their life…. More often than not, although withdrawal symptoms are uncomfortable, they are not life threatening,” Shah’s email continued. “Emergency departments become in a way suboxone/methadone clinics as patients can find coming to the [emergency department] the most convenient way to treat their withdrawals.”

While some physicians may be reticent to provide treatment for medical reasons, their own stigma towards addiction may be just as big a barrier.

“Lack of knowledge and fear of the unknown are big factors, and the other is stigma,” said Littleton. “People get concerned about [treating] the patient who has an addiction and what that means.”

Some providers worry that treating addiction is like “opening up a Pandora’s Box,” said Littleton. They think “if we talk about [your addiction] we’re going to talk about all that trauma that you had as a child and I don’t have the resources to give you the support to deal with that, I don’t have access to good mental health [services] that I can connect you with… and I can only address so many things in 15 minutes.”

Littleton walks through these traumas with almost every patient she sees. Raymond, who had recently been released from Rikers on drug charges and asked that his last name not be used, told Littleton that he’d been using speedballs (a mixture of heroin and cocaine) since age 11, when his father introduced him to the dangerous cocktail.

Littleton didn’t blink when Raymond said that he’d had a relapse. Like Salvador, he relied on heroin to tide himself over after leaving prison, before coming for treatment. Instead of discharging patients who relapse, punishing “dirty urine” by terminating treatment, Littleton stresses the importance of patience and understanding.

“Many [patients] will have a relapse, and that’s okay,” she said after seeing Raymond out. “Addiction is a spectrum… [and] we do them a disservice by discharging them.”

Once physicians can normalize their understanding of addiction, and see the effect of treatment, those fears and stigmas will fade, Littleton said. “It’s just understanding that… anybody can have opioid use disorder and have perfectly normal lives otherwise.”

Treating opioid addiction is no simple task, and buprenorphine is not a silver bullet, said Lu, the doctor from Montefiore. But, access and supply are the only way to get this life-saving drug into more hands.

“[Being trained to prescribe] buprenorphine is the lowest threshold that anyone can do.” Lu said. “My message to all my colleagues is: please do something, get yourself trained, offer it, because if you don’t offer it you’re basically saying you’re not interested in treating the disease in any way.”