Charles Aviles, a 36 year-old Bronx resident, will always remember his mother’s childhood friend Ronnie when he thinks about growing up during the 1980s. Ronnie had treated Aviles like a son, helping him with things like tying his sneakers.

“He had one of those million-dollar smiles, like nothing ever bothered him,” he said.

But when Aviles was just 10-years-old, Ronnie passed away suddenly. That was when Aviles first became aware of AIDs. The global epidemic continued to rage throughout Aviles’s childhood years and into the early 1990s.

HIV and AIDs rates have decreased globally since the peak of the epidemic in the 1980s, and earlier this month, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced that the number of HIV diagnoses in the state had declined by 28 percent since 2014. But that doesn’t mean progress is evenly spread: just as the Bronx was disproportionately affected during the crisis’s peak, today it is one of the Center for Disease Control’s 45 HIV hotspots across the country.

There are several factors that feed into the “invisible crisis” of HIV in the south Bronx, according to Dr. Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, director of the Center for Latino Adolescent and Family Health. HIV rates are higher among Latino and African American populations, which disproportionately populate the borough. There are also generally higher rates of HIV among men under 25 years old, particularly those who are gay and bisexual. The Bronx also has the largest youth population of any of New York’s five boroughs. Language and cultural differences also play a role.

Both government and non-profits have been trying to address the issue with outreach programs tailored to specific demographics.

For example, hair care professionals were one of the groups identified by the CDC as potential partners for its Business Response to AIDs initiative, which began in 1992. The program partners with businesses, health departments, community based organizations and government agencies to provide public education on HIV. As barbers in New York are already required by state law to receive training on contagious disease transmission associated with their professional duties, training centers for hair care professionals were an obvious group to incorporate into the program.

Aviles, who is training to become a barber at the Beyond Beauty & Barber Academy in the Bronx’s Westchester Square neighborhood, is also being trained to talk to people about HIV. For Aviles, it’s important not just to have practical knowledge about safe barber practices – sanitizing equipment, taking care with pimples and open wounds – but also about how the community provided by space can facilitate difficult talks.

“Barbershops are the places where you let loose, where you want to be able to talk sometimes and at home you can’t really have certain conversations,” he said. “But when the fellas are around, it’s a great environment to have certain conversations.”

But despite efforts like the CDC’s, there are several reasons that HIV rates remain high across the Bronx today.

There are fewer health services in the area than elsewhere in the city, and Latinos and African Americans are disproportionately uninsured, or have inadequate coverage. For many, that means that PrEP, a highly effective antiretroviral drug, often isn’t available to them. Bronx residents generally have lower incomes than in other parts of the city, Dr Guilamo-Ramos said, and other expenses might seem more urgent than medication for a chronic health condition.

People also feel scared about going into formal spaces like hospitals or clinics to take an HIV test test, said Daniel Leyva, the Latino Commission on AIDs’s press secretary. This discomfort can be especially prevalent among Latinos and people of color, who can feel socially and culturally excluded in places like sexual health clinics.

“It’s really sad to see that a lot of people in our community are still dealing with so much stigma,” said Ivan Ribera, a community engagement specialist at Latino Pride Center whose daily work involves approaching people to talk about HIV prevention.

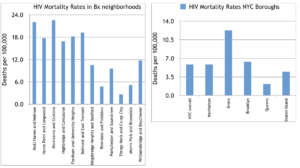

All of this has grave consequences for the Bronx. The borough’s rate of premature deaths from HIV was twice as high as the New York City average in 2018, according to Community Health Profile data., which put the Bronx’s rate at 12.3 deaths per 100,000 compared to Brooklyn’s 6.4 and the New York City average of 5.9. In total, the Bronx saw 792 premature deaths from HIV last year.

Moreover, the South Bronx itself is a pocket with much higher HIV death rates than anywhere else in New York City. Morrisania, Mott Haven and Hunts Point were among the worst-affected areas.

Dr. Guilamo-Ramos has piloted a number of pioneering outreach and education programs in recent years, but described youth infection rates as a “raging epidemic”. As a result, two of the programs he runs – Families Talking Together and Fathers Raising Responsible Men – target teenagers and work with families to communicate on the issue.

Ribera said he talks to approximately eleven people a week on an individual basis as part of his outreach work, and that much of it involves trying to get people to use condoms. “There’s this idea that NYC condoms don’t work,” he said, alluding to rumors that condoms issued by the city’s Health Department are faulty. “So we try to push condoms, to eliminate those patterns.” In addition to approaching people in the street, Ribera and the Latino Pride Center produce discreet boxes filled with a range of differently-sized and -flavored condoms and leave them in places like barbershops.

Churches are another space being leveraged to offer a culturally-specific outreach service, due to their standing in minority communities and the close personal relationships they often cultivate in areas such as the Bronx.

“Churches are becoming a mediator between communities and its services people who are nervous about seeking services somewhere else,” said Leyva, adding that they can be particularly important for people who don’t see themselves as a part of at-risk groups or who don’t realize the breadth of health services they are entitled to use. “At the end of the day, it’s about promoting safe spaces for people to discuss sensitive issues.”

In Aviles’s mind, the necessary outreach work to combat HIV in the Bronx shouldn’t pose as many challenges as it appears to. “It doesn’t mean you got the cooties or anything like that. You’re just a normal person,” he said. “Things happen.”

![[Video] An Easter tradition thrives in Tremont](http://bronxink.org/wp-content/themes/gazette/functions/thumb.php?src=wp-content/blogs.dir/3/files/2011/04/000_0072_01.jpg&w=100&h=57&zc=1&q=90)