Zachary Cassel, The Bronx Ink

Elizabeth Thompson, a 72-year-old retired health care clerk, had been in and out of housing court since 1988. Usually, it was because her landlord claimed she was behind in the rent.

It was a battle that Thompson largely fought on her own. Until recently.

This past March, Thompson’s landlord took her to court again because she owed $817 in rent, according to court documents. Thompson is on a fixed income from social security and it doesn’t always arrive at the same time, she said. At first, she represented herself.

But she faced little success in court and decided she needed a lawyer.

“They say I’m not qualified for a lawyer,” she said.

Thompson received too much money in retirement from social security to qualify for a free lawyer in housing court, but she couldn’t afford one on her own.

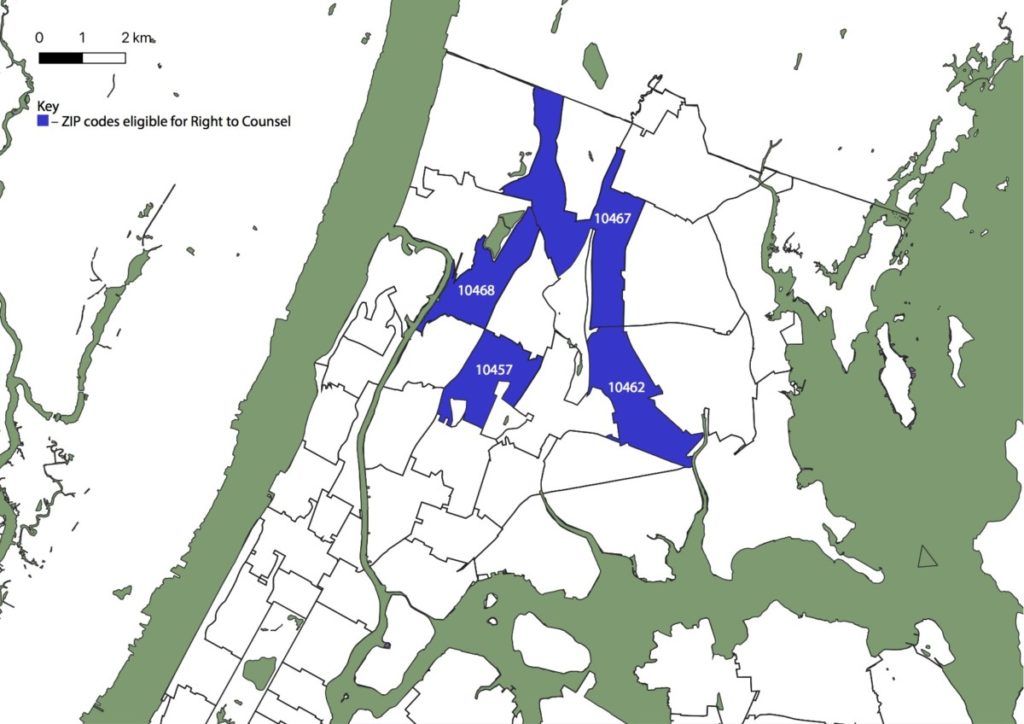

New York City passed its historic Universal Access to Legal Representation law, also known as Right to Counsel, in 2017. It ensures free legal services to low-income Bronx tenants living in four ZIP codes, 10457, 10462, 10467 and 10468. In just two years, evictions in the Bronx decreased by 23%, according to the New York City Office of Civil Justice Annual Report. In a city where two-thirds of residents rent, the Bronx claimed the highest decrease in evictions since Right to Counsel was implemented.

Hibah Ansari, The Bronx Ink

The Right to Counsel NYC Coalition advocated for the law. They’re now campaigning to expand it so that more tenants, like Thompson, can be eligible. They partner with other organizations like Legal Services NYC.

Right to Counsel gives power back to tenants, especially as they face landlords represented by powerful law firms, according to Heejung Kook, the housing unit deputy director for Legal Services NYC.

“No one really gives advice to the tenants,” Kook said. “Once the attorney gets involved through the tenant’s side, the tenant knows what their defenses are. So we can try to negotiate for better terms, or often just to fight hard to keep their apartment.”

Thompson asked the Northwest Bronx Community Clergy Association for help, and they directed her to the Legal Aid Society. Although she didn’t qualify because her income was too high, she spoke with a supervisor and was approved anyway.

Everything changed after she found representation, Thompson said.

“The court lawyer went against our landlord’s lawyer and let him know that he had to do,” she said.

Nadia Hasan, the supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Society NYC, took up her case.

“A lot of it has to do with just having someone on your side, someone listening and explaining things to you,” Hasan said about Right to Counsel. She added that tenants also get better terms with an attorney present.

Both parties have to comply with the agreement Hasan fought for — Thompson will follow a payment plan while the landlord addresses the repairs.

Brian Stark, a lawyer for her landlord, according to court documents, could not be reached for comment.

The Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition is a grassroots social justice organization. Part of their mission is to advocate for tenants’ rights in the Bronx.

The Bronx has had the most evictions out of any borough for the last six years, according to the Office of Civil Justice report. Before the law was passed, city marshals carried out 7,438 evictions in the Bronx, compared to 5,984 eviction in Brooklyn and 2,843 in Manhattan.

To qualify for free legal services, a family of two would have to make an income of less than $32,480, according to the New York City Housing Court. Thompson earns about $40,000 per a year.

The Right to Counsel NYC Coalition wants to increase the income eligibility so more tenants like Thompson can be covered. For a family of two, the income limit would be $67,640.

Thompson’s building is owned by Claflin Apartments LLC, which is registered to Moshe Piller, according to state business records.

The Bronx Ink previously reported on the conditions of Piller’s buildings in Brooklyn and the Bronx in 2010. At the time, tenants complained of faulty wiring, a collapsed ceiling and clogged plumbing.

Thompson, who’s lived in the same Fordham apartment for 35 years, had similar complaints about her apartment.

Some days, the boiler in the building worked. Other days it didn’t. The electricity would occasionally go out — one time for eleven hours. Mice came through a hole under her kitchen sink.

Inell Tolliver, 57, also lives in Thompson’s building. Tolliver said that the other tenants wouldn’t know how their landlord was responding to violations without Thompson, who tried to set up a meeting with building management.

There have been 286 complaints registered against Thompson’s building since 1991, according to the Department of Buildings. There have been nine since January. The most frequent complaint is that the elevator stops working. The building has six floors.

The superintendent could not be reached for comment.

Tolliver cited mold, scraped floors and a locked laundry room in the basement. She also said that the hot water doesn’t always work and it’s been a recurring issue.

When the Bronx Ink tested Thompson’s sink, the water became warm but would not get hot.

Neither Piller or a representative from M. P. Management could be reached for comment.

By 2022, all tenants who are income-eligible in New York City should have access to free legal representation, according to the New York City Housing Court. But even now, as evictions are decreasing, more than half of the tenants at the Bronx Housing Court did not know about their eligibility for a free lawyer before arriving to court, according to a survey conducted by the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition.

For the first time, funding for expansion of legal services for low-income New York City tenants exceeded $100 million in 2018. The city expects to increase funding until all low-income tenants are covered in 2022, according to the Office of Civil Justice. Legal Services NYC also receives funding from the federal and state government as well as charity organizations.

Kook has some doubts about Right to Counsel’s ability to expand to all ZIP codes by 2022. But she added that if the city continues to fund and support Right to Counsel providers in the long term, they can effectively expand their services and decrease evictions across the city.

“Anyone can change the law,” Kook said. “We’re really hoping that the city will continue doing this kind of work.”

Thompson has not been to court since July. Her attorney helped her reach an agreement that will keep her out if she keeps up with rent.