Mice, roaches, leaking pipes, and bulging walls — one of these alone could be a tenant’s nightmare. Andrea Daniels, a long-time Bronx resident, lives with all of them.

Daniels has lived in her rent-regulated Mott Haven apartment for 16 years. When she needed repairs to her apartment, Daniels put in requests with her landlord. But many went unaddressed, she said.

The city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) issues violations against apartments that don’t comply with the housing code, whether during routine inspections or when a tenant alerts the agency. In some more extreme cases, financial penalties may accompany violations. For Daniels, however, HPD was of no help; in total, her apartment has been issued 119 violations, 86 of which remain open, as listed on HPD’s database. Yet the problems persist. That’s how Daniels ended up in Bronx Housing Court in June.

Daniels is suing her landlord for repairs in housing court. Her case is what’s known as a Housing Part (HP) action, which falls under section 110 of the City Civil Court Act. Nearly every month since her case began, Daniels has returned to court, often spending an entire day there. The 41-year-old has a disability and sometimes misses doctor’s appointments because she has to appear in court.

Each time, she meets with an HPD attorney, her landlord’s lawyer and a judge. Together, they attempt to avoid trial by negotiating the terms of a mutual agreement that aims to correct the violations.

In theory, once all the parties have reached an agreement, they must do what the judge stipulates within a set time frame.

During a court session on June 26, Daniels, her landlord’s lawyer and the HPD attorney set up July “access dates” — days on which the landlord must send workers — to “correct all violations,” or make the repairs, according to court documents. But on those days, Daniels said, no one came.

During an August court date, court records show the access dates were rescheduled for September. On one of those access days, one exterminator arrived, Daniels said, though court records show seven violations that needed correcting. According to Daniels, her landlord argued the workers came, but no one answered the door.

Daniels’s landlord, Sharp Property Management, and the law firm representing the landlord did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

At her next court appearance, her landlord’s lawyer informed Daniels they were drawing up a holdover case against her for denying workers access to her apartment. Such cases are filed when a landlord sues to evict a tenant regardless of whether or not she pays rent.

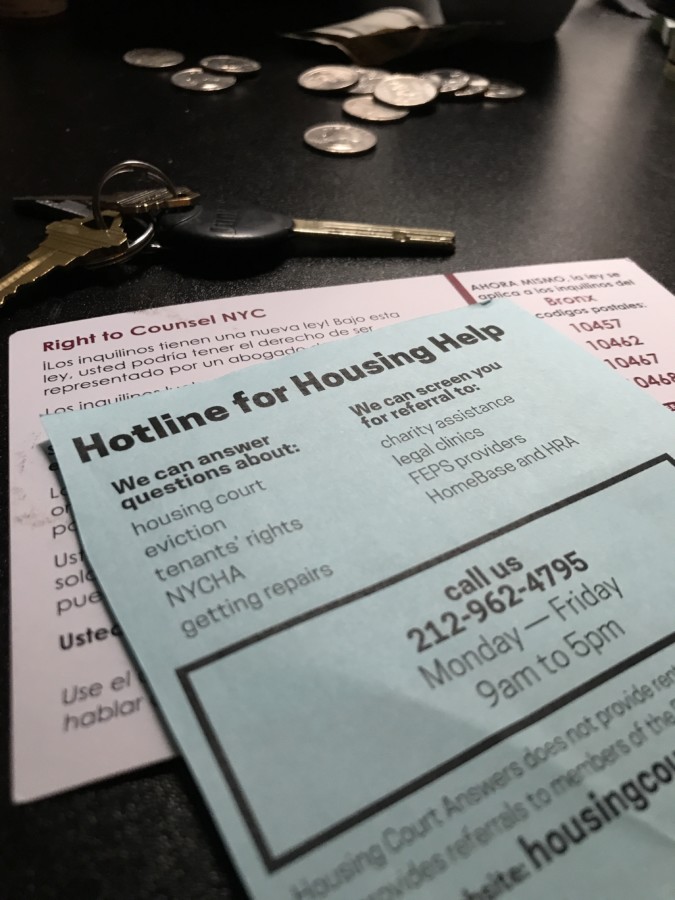

Housing Court Answers, a local nonprofit that works with tenants and small homeowners to inform them of their rights in the judicial process, has witnessed HP cases since the organization’s inception in 1981, said assistant director Jessica Hurd. Involving HPD is almost always an ineffective way of getting repairs done or violations corrected, according to multiple representatives of the organization.

The only real purpose of reporting to HPD is to have an on-the-record trail of complaints, said Pedro Ariel Dominguez, the Bronx borough coordinator at Housing Court Answers. The city agency can issue penalties, or fines, but according to Dominguez, rarely does.

HPD admits as much.

“We issue violations, not fines. But some violations come with penalties,” a spokesperson for HPD said.

Civil penalties are various fees demanded of the landlord, the price of which depends on the degree of the violation.

Genesis Aquino, Housing Court Answers’s NYC housing authority program coordinator, explained the flaws of the litigation process that make it difficult for tenants to navigate the judicial system. Typically, tenants seeking repairs withhold rent with the hope that their landlord will be pressed to make repairs, she said. Many don’t know they can take the landlord to court with an HP action, or that the case will be stronger when more than one tenant signs on.

“The court has never been pro-tenant,” Aquino said.

The strength of the case also depends on how well each party represents themselves, or hires someone to do so. Many tenants can’t afford legal counsel, nor do they understand the policy nuances to fend for themselves. To add to the burden, it’s the tenant’s responsibility to bring the case back “on calendar,” or back to court, if the landlord violates the agreement that was reached in the courtroom.

“If you’re not on top of it, nothing’s going to happen with an HP action,” Aquino said.

A spokesperson for HPD disagreed. The agency can issue multiple violations for the same problem, and those violations won’t be cleared from the record unless they are corrected. In court, “all that is stacked against the landlord,” an HPD spokesman said.

Ferdo Shkreli, a property manager of five buildings in the Bronx, said he welcomes the HP process.

“It helps me, otherwise my building deteriorates,” he said, adding he actually encourages tenants to file an HP case so they can resolve it in court.

HP cases can also benefit tenants because they will have more enforcement options, according to housing attorney Robert Farina. In Farina’s experience, it’s “an effective way of getting repairs done.”

“They get settled and that’s usually the end of it. Everyone’s usually happy,” Farina said.

In some cases, HPD, rather than a tenant, brings an HP case against a landlord. Shkreli, who fights on behalf of small landlords accused by the agency in court, suspects doing so is the agency’s way of going “after the landlord’s pocket.”

HPD knows a small landlord cannot afford the costs that come with going to trial, unlike big landlords who have in-house attorneys, Shkreli explained. In a recent case he settled with HPD, the agency demanded civil penalties totaling $800, which Shkreli paid in order to avoid going to trial. In some settlement cases, he said, even after he paid, and even with proof of the repair, the violation(s) in question remained open.

“It’s cheaper to pay a fine than go to trial,” Shkreli said. “Whether you fix it or don’t fix it, they’re still going to issue a fine. That’s how they twist the landlords’ arm.”

In order for a corrected violation to be taken down and no longer listed as open, a landlord or property manager like Shkreli must file a dismissal request with HPD, which costs upward of $1000 to submit, according to the agency’s policy.

HPD issued a total of 643,200 violations in 2018 alone, the agency told The Bronx Ink.

Daniels, who has been in and out of court for months and is still in need of multiple repairs, has lost her faith in HPD and the process.

“They give [landlords] too many chances to do the repairs. I can’t take a year to pay you your money,” she said, referencing laws mandating tenants pay their rent in a timely manner. But, when it comes to repairs, tenants’ cases can drag on in court, sometimes for years.

“I just feel like the law is not really on the tenant’s side, especially when it comes to HP cases,” she said.